Ranchero music is an essential part of any self-respecting fiesta—the mariachi with their fitted pants, short boots, and wide-brimmed sombreros. Every Mexican knows the immortal themes of the genre, such as “Guadalajara or Caminos de Guanajuato,” which sing the glories of the Mexican province.

But while the bucolic towns of the Mexican Bajío may be too foreign for Americans of Mexican ancestry living on the northern side of the border, thanks to Lalo Guerrero, anybody can listen to authentic mariachi songs.

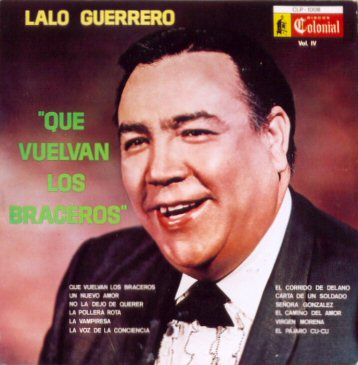

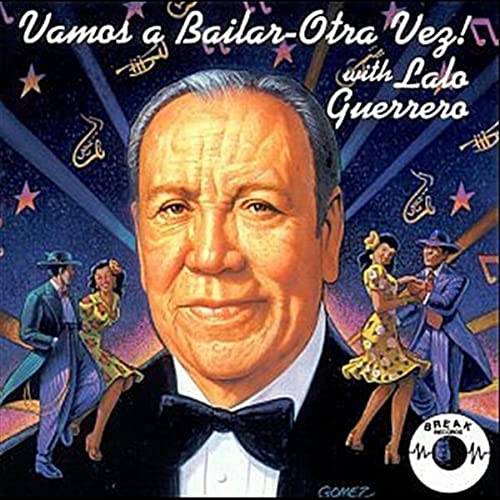

The Father Of Chicano Music

Lalo Guerrero, a forgotten figure in Mexico and little remembered in the United States, is the father of Chicano music. During a career that spanned more than seven decades, he sang about the experience of the Chicano and the Pachuco subculture in songs like, “There’s no tortillas and Los Chucos Suaves.”

“He’s singing my biography, and he doesn’t know it!” a listener with whom I shared some of his songs told me while I was writing this article.

Long before the Chicano movement existed, Lalo acknowledged the joys, existential conflicts, and social dilemmas faced by the Mexican American population in the States.

In the 1950s he caught the spirit and slang of the Pachuco subculture. He was the first to write and record songs using slang to the cadence of swing, boogie boggie and mariachi.

There’s no tortillas

A son of immigrants, Guerrero was the product of what would later be called Chicano culture, having been born in a neighborhood in Tucson called “Barrio Viejo” which was neither Mexican or American, but a blend of them. His family was poor. His mother, Concepción, taught him his first repertoire and encouraged him to play the guitar.

In his youth, Guerrero went on to play with several groups in Tucson in the 1930s and his first recordings were made in LA in 1939.

Legend goes that producer Manuel Acuña saw him playing in the street and asked him if he was a musician. The next day they were in the recording studio.

Guerrero’s first important song, “Canción Mexicana,” a favorite of his, was long considered a kind of Mexican national anthem of the Mexican diaspora.

This lyrical tribute to Mexican music “was a kind of gift to the people of my old neighborhood to remind them that, even if we were poor, we had something to be proud of,” said Lalo during an interview.

“El Corrido de Delano,” an activist song with northern Mexican style was inspired by the fight of César Chávez. He sang both in English and Spanish, sometimes in the same track—a first.

“Maybe we should recover Guerrero’s lighthearted humor, considering that one distinctive mark of the Mexicans is to laugh at themselves.”

One of his favorite artistic expressions was parody. He sometimes took songs from the public domain to tell stories. In “No way, Jose” he humorously recounts the difficulties of migrant workers crossing the border, (“No way, Jose, if you don’t got no papers you don’t go to USA”).

In “There’s no tortillas,” a song in the line between comedy and real-life drama, which he allegedly wrote after waking up starved, he sang “I love tortillas and I love them dearly, you’ll never know just how sincerely, I love the corn ones, but when Mama cries out from the kitchen, ‘There’s no tortillas…’”

Decades before the counterculture of the 1960s, he sang “Marihuana boogie” while not forgetting the simple pleasure of being a Chicano (“Los Angeles, under your sky we live at peace, a million Mexicans. My Virgin of Guadalupe, we adore her here as they do over there…”).

Later in life, he criticized the negative portrayal of Latino culture on the media: “There are Chicanos in real life, doctors, lawyers, husbands, wives, but all they show us on TV, are illegal aliens as they flee.”

From “Pancho Lopez” to “Las Ardillitas”

His first hit on the mainstream charts was a parody of the Disney theme “Davy Crockett,” which he re-named “Pancho Lopez,” a song about a glutton and lazy Mexican who fights with Pancho Villa in the Revolution but deserts the army and ends up putting a taco stand on L.A.’s Olvera Street.

It is an exquisite song—Mr. Walt Disney himself praised it—but political correctness has condemned it to an anecdote, or to essays by scholars and institutions.

In the 1970s, some of his songs were featured in Luis Valdez’s Broadway musical “Zoot Suit,” the ultimate Chicano play.

In that same decade he came up with Las Ardillitas, the squirrels—apparently a mexicanization of Alvin and the Chipmunks—which were a sensation in Mexican radio in the 1970s, a bittersweet success in the country he so much lauded in his song, but had ignored him so far.

“After all those years of banging on doors,” Guerrero said, “I finally got to record in Mexico City… as a squirrel.”

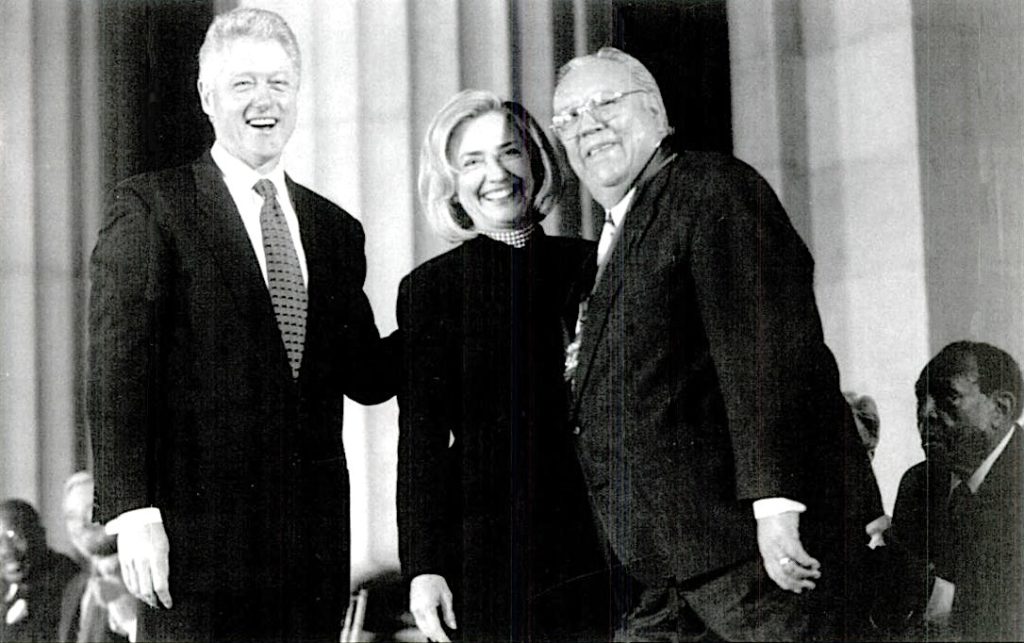

In the next decade true recognition began for Lalo. In 1980 he was invited to the White House by First Lady Rosalynn Carter, he was declared a National Folk Treasure by the Smithsonian Institution, and President Clinton gave him the National Medal of Arts in 1996, the highest honor given to artists.

It was a long journey from the poor barrio in Tucson and no formal music education. After having written more than 700 songs, Lalo González, the original Chicano, died at the age of 88 in California.

Always with a smile

Lalo Guerrero’s music had a praiseworthy quality: it was never negative. It still makes us smile, as if despite the pain, discrimination or struggle, Lalo always bet that humans can have a sense of humor and are still able to laugh at the disgrace.

The characters of his songs refuse to be victims. The lyrics are never preachy or bitter. Guerrero always had a smile on his face even as he sang the saddest truths of life.

He was surprised when “Pancho Lopez” began to be considered a racist song, and he stopped singing it in public, but the lesson here is maybe we should recover Guerrero’s lighthearted humor, considering that one distinctive mark of the Mexicans is to laugh at themselves.

“Over the years, some of my songs have offended different groups: “I have never intended any malice or meanness, but I’ve never worried much about being politically correct. I just find humor in everything.”

That’s true Latino spirit!

Download The Daily Chela TV App

Download the new Daily Chela TV app on Apple IOS, Android, or Roku.