My decade as a member of a Mexican American street gang was explosive. I learned how to fight. I learned how to dodge bullets. I learned how to elude police. Yet despite the intimidating glares, shaved heads, and tattooed faces, there was something strangely endearing about the gang members I knew. Something far more complex and closer to home than most people realize. A world brimming with classic cars, music, and art.

Something unmistakably American like Apple Pie.

Understanding the origins of Mexican American street gangs (and the Central American street gangs they influenced on the surface) is crucial to curbing the violence often associated with them. Contrary to portrayal, the world’s largest street gangs not only originated on American soil in response to widespread discrimination and rampant nationalism, but spread to the rest of the world as a result of overactive immigration policies. And until the federal government acknowledges the failure of these policies, the true catalyst behind these problems can never be addressed.

War and Nationalism

You can’t talk about street gangs without talking about Mexican American street gangs, whose American origins run deep. Unlike white and black gangs, Mexican American street gangs transcend economic class, geography, and even centuries. In fact, some of the oldest Mexican American cliques date back to the late 1890s (Dog Town Rifa, for example), roughly 70 years before the Crips or Bloods, and almost 30 years before the first Outlaw Motorcycle gang.

Many of these same cliques not only still operate in the same neighborhoods, outlasting both the Irish and Italian gangs that began at the same time, but have withstood repeated attempts by the federal government to root them out (38th Street, Big Hazard, and White Fence, for example). It’s an impressive feat. However, if you understand the cultural impact Mexican American gangs have had on American gang culture—and American culture in general—it’s not surprising.

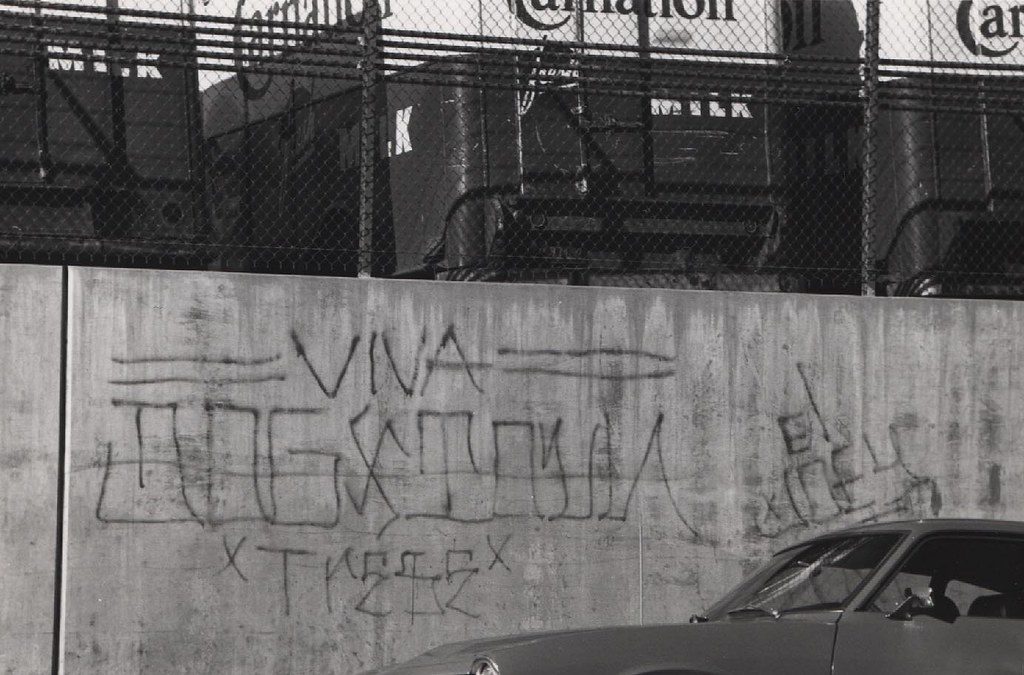

As Leon Bing wrote in her book, Do or Die, which Luis J. Rodriguez subsequently quoted in his famous memoir, Always Running: “It was the cholo homeboy who first walked the walk and talked the talk. It was the Mexican American pachuco who initiated the emblematic tattoos, the signing with hands, the writing of legends on walls.”

But the cliques of the early 1900s weren’t the violent criminal street gangs we know today. Forced into segregated communities and widely discriminated against during a time when the American Southwest was in the middle of a turbulent transformation, young Mexican Americans primarily banded together out of self-preservation and common interests—not criminal intent. Some found identity through family surnames and close-knit neighborhoods. Others found brotherhood through car clubs and the zoot suit subculture of African American jazz music.

Seeking respect and recognition, Mexican American Pachucos openly adopted the flamboyant “wide-legged” style associated with zoot suits. But as nationalist sentiment soared, American sailors began hunting down and attacking Pachucos over social and cultural differences. On one hand, sailors considered zoot suits to be unpatriotic during a time of war rationing. On the other, sailors viewed Mexican Americans as traitors and invaders despite being born in the United States.

Tensions eventually boiled over following a highly publicized incident at a popular swimming hole known as “Sleepy Lagoon” in Southern California. During the incident, a young Mexican American named José Díaz was found stabbed with a fractured skull on the side of the road. He later died. Following his death, widespread panic ensued, and officials began labeling all Pachucos and groups of young Mexican American males as criminal “gangs.” In response, the government rounded up some 600 Mexican Americans across Los Angeles, culminating in the wrongful conviction of 17 Mexican American youth, and later spawning the infamous Zoot Suit Riots.

“As drugs flooded the streets…and divisions between neighborhoods grew, rivalries intensified. Cliques became gangs. Barrios became war zones.”

The incident at Sleepy Lagoon in 1942 and subsequent Zoot Suit Riots in 1943 were major flash points in the evolution of modern Latino street gangs. Following the riots, distrust of law enforcement skyrocketed, and Mexican Americans began protecting their neighborhoods from outsiders the same way outsiders had protected their neighborhoods from them. Worse, as drugs flooded the streets a few decades later and divisions between neighborhoods grew, rivalries intensified. Cliques became gangs. Barrios became war zones. The modern day Cholo (a Mexican American gang member) was born.

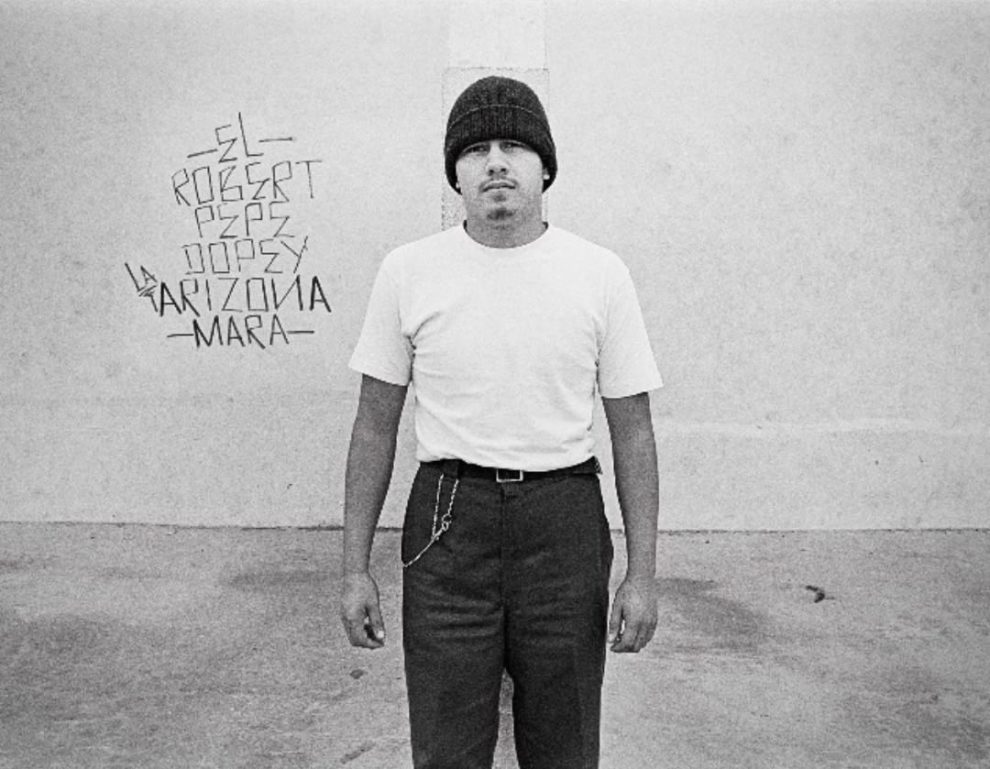

In 1943, all of the pachucos from the incident at Sleepy Lagoon had their cases overturned and reentered society (see People v Zammora 66 Cal.App.2d 166). These pachucos would go on to become heroes across Los Angeles. Some have speculated—including myself—that this is where the fashion of the California state prison system would go on to mix with the pachuco fashion of the 1940s—laying the foundation for one of the most recognizable and distinct gang fashions today (white t-shirts, creased pants, shaved head, dark sunglasses etc.).

Failed Immigration Policies

Throughout the mid and late 20th century, Mexican American street gangs grew in sophistication, adopted distinct customs and—contrary to widespread belief—initially discriminated against immigrants from Mexico and Central America. As a result, many immigrants were forced to adopt American gang culture or form their own gangs to survive.

This divide, and the debate over whether immigrants from Mexico or Central America should be allowed to join Mexican American gangs, ultimately led to the formation and growth of some of the largest transnational gangs in the world—each which recruited immigrants and went on to expand beyond the confines of their traditional neighborhoods.

Divisions escalated both on the streets and in the prison system. On one hand, Mexican American gang members viewed Mexican and Central American immigrants, many who had fled to the United States to find work, as unsophisticated and subservient. On the other, immigrants viewed Mexican American gang members as “Americanized Hispanics”—or Pochos—who had forgotten their culture and roots.

In response, the federal government implemented strict mass deportation policies, not too unlike policies advocated today by conservatives. But the move was rash and didn’t take into account the complex social constructs of gangs. As a result, the federal government not only failed to curb gang activity in American cities like Los Angeles, but exported American gang culture to places it had never previously existed—places like Mexico, Honduras and El Salvador.

While in Mexico, gang members lost stature due to local aversion and powerful cartels, in places like El Salvador—which was in the midst of a bloody civil war at the time—gang members became militarized and empowered. Today El Salvador is home to over 60,000 militarized gang members—none that existed until the United States exported American gang culture. Now, thousands of innocent civilians attempt to escape the violence each year, which claims more than 3,000 lives.

American As Apple Pie

Some of these same gang members have since tried to return to the United States, leading politicians to believe that deportation is again the answer. But it isn’t. The truth is undocumented gang members represent a minuscule fraction of total gang membership in the United States, and Central American gang members represent an even smaller faction. For perspective, Los Angeles county alone still remains home to more than 50,000 gang members—the majority of which are not Central American.

“Since the 90s, one could argue that Mexican American gang culture in the United States has become a lucrative pop culture phenomenon at the demand of American consumers.”

Too often, the media generalizes gang members of Latino origin, lumping Mexican American and Central American gang members into one phenomenon. But while central American gang culture was certainly influenced by Mexican American gang culture on the aesthetic level (as many gangs have been), the two have very different histories. More importantly, the two come from two very different social environments, and operate by sets of very different rules.

Since the 90s, one could argue that Mexican American gang culture in the United States has become a lucrative pop culture phenomenon at the demand of American consumers. On social media, YouTube shows such as “Cholos Try” have amassed huge followings and landed television deals. In music, Chicano rap has spawned hundreds of artists and record labels. And in film and apparel, major multinational corporations ranging from Warner Bros to Nike have commissioned artwork from Mexican American artists whose style reflect Chicano gang culture.

Like most things that involve capitalism, the result has been a double-edged sword. On one hand, the advent of technology has probably done more to curb gang violence than any government program. On the other hand, it has also watered down many other aspects of Chicano culture, while perpetuating stereotypes.

The Trump administration didn’t help. Like the 1940s, hysterics and a new wave of populism have again led to discrimination and dangerous nationalist rhetoric. With this, facts have been skewed and statistics muddled. But context is crucial. Though gang violence has spiked in recent years, it has plummeted over the past two decades, largely due to non-profit outreach, and the advent of technology. In fact, one could argue we are living in one of the most peaceful times in history.

This doesn’t mean gang violence doesn’t exist. It does. But before addressing gangs, we must first start with addressing the underlying social conditions that produce and fuel gangs, which begins by first acknowledging the failures of past government policies and sentiments. It was the Pachuco roundups of the 1940s and deportations of the 1990s, after all, that resulted in the unintended consequences we continue to deal with today. How much sense does it make to repeat them?

After all, cholos are as American as Apple Pie.