One of the great pending tasks in writing the history of World War II is the recognition of Chicanos and Latinos in general. Many Mexican Americans who were on the north side of the border in the 1940s fought bravely and stood out for their heroism.

But possibly none have risen to the greatness of Guy Gabaldon, the Chicano who singlehandedly captured 1,500 prisoners during the invasion of Saipan in the Pacific.

The Battle of Saipan has been called the D-Day of the Eastern Front for its strategic importance. However, on the day of his greatest feat, Gabaldon was only 18. And he didn’t fire a single shot.

But how did he do it?

His Japanese family

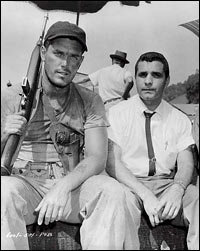

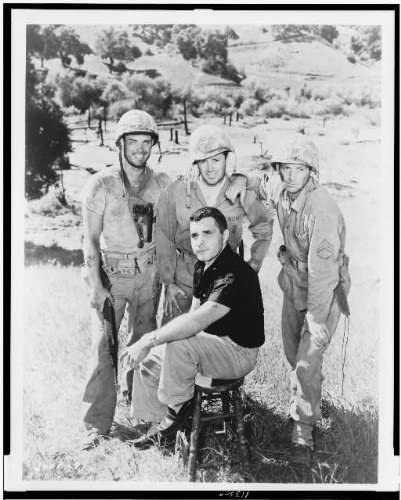

Gabaldon’s story is so extraordinary that Hollywood made a movie about his life in 1960, called Hell to Eternity. Ironically, the young Chicano was personified not by a Mexican or Hispanic artist, but by tall, blue-eyed Jeffrey Hunter, a 33-year-old actor of Scottish descent.

The real Gabaldon was 5’4” (162 cm) and still a teenager when he joined the army. Not that Guy was upset about it. “Jeffery (Hunter) was jealous that he didn’t have my good looks!” he used to say jokingly.

Gabaldon grew up in a difficult time and place: the Great Depression years in the East Los Angeles barrios. His family was poor, but he didn’t notice it, saying, “we always had beans and tortillas.”

The boy helped the family make ends meet shining shoes in the hazardous streets of East L.A., where he developed survival skills.

“Fighting in the Pacific tropical jungles and living in the East Los Angeles ghettos had a lot in common —you had to be one step ahead of the enemy, or adios mother!”

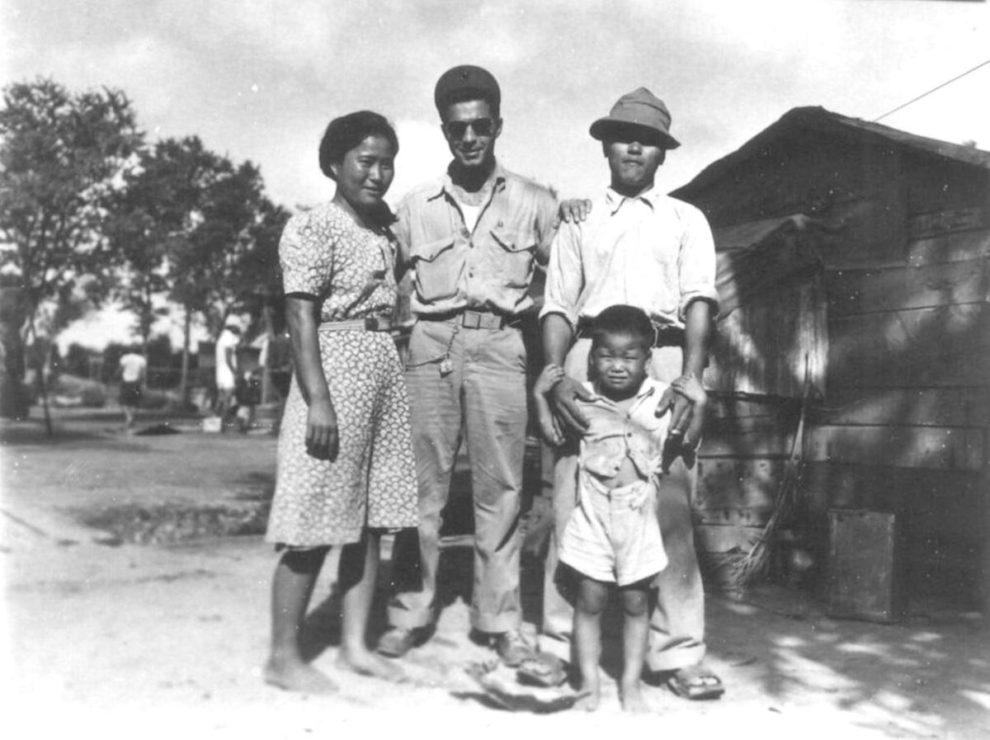

At the age of twelve, Guy became friends with a Japanese family, the Nakanos. The Nakanos took him as a son. There he learned to speak Japanese, an ability that would save his life six years later.

In “Street Japanese”

Guy tried to join the army when he was 16, but he was rejected. The Marine Corps took him the following year. In July 1944, he was in the Battle of Saipan in the Mariana Islands. As a scout, he could move freely.

Guy shot two guards at the entrance of a cave, stood outside and screamed with his “street Japanese” that they were surrounded and should surrender, and that they would be treated with respect.

His negotiation skills must have been extraordinary. Following the same tactic, he brought dozens of prisoners to the camp on several occasions during that summer.

On July 7 or 8, at the cliffs, he captured two Japanese guards. He cooled them down and convinced one of them to go back to the caves where the rest was hiding along with some civilians, and surrender.

“Why die when you have a chance to surrender under honorable conditions?” he asked them. “You are taking civilians to their death, which is not part of your Bushido military code.”

Guy knew that he was taking extraordinary chances. The hundreds of soldiers in the caves below could simply go up where he was and shoot him, a single American soldier trying to give them orders. Or he could get away with the most astonishing feat of war times.

“I am here to bring you a message from General Holland ‘Mad’ Smith, the Shogun in charge of the Marianas Operation”, he told the hundreds of scared, altered Japanese soldiers as they went up to meet him.

In an interview with War Times Journal in 1998, Guy remembered the exact words:

“General Smith admires your valor and has ordered our troops to offer a safe haven to all the survivors of your intrepid Gyokusai attack yesterday. Such a glorious and courageous military action will go down in history.

“The General assures you that you will be taken to Hawaii where you will be kept together in comfortable quarters until the end of the war. The General’s word is honorable. It is his desire that there be no more useless bloodshed.”

He then offered them cigarettes and he asked them to sit down.

When a unit of the U.S. army found Guy with the 800 Japanese, most of them still with their guns, ordering them into smaller groups, his comrades thought that he had been captured. In reality, the Japanese had surrendered en masse to the boy from East L.A., an astonishing number considering that the Japanese soldiers fought with fanatical drive and preferred to commit suicide rather than capitulate.

Guy goes to Hollywood

For years, the exploits of Guy Gabaldón were not known until his friends began to talk about him on TV. In 1957 a film company bought the rights to Guy’s life and two years later filming began in Okinawa. Guy, a technical advisor, was impressed by Jeffrey Hunter´s acting. They became good friends and Guy named his son Jeffrey after the actor.

When Hell to Eternity premiered, Guy received the Navy Cross, although many felt that he deserved the Congressional Medal of Honor, the highest recognition.

“I recommended him for a Congressional Medal of Honor,” said Col. John Schwabe, Gabaldon’s commanding officer during the war. “I thought it was just an unbelievable feat, for a kid like that to do something like that.”

But again, Guy was a Chicano, and raised by a Japanese family. And it was 1960, a whole different era.

“Of course (I didn’t receive the Medal of Honor) because I am a Chicano”, Gabaldon told Maggie Rivas-Rodriguez, who interviewed him in 2000 for the Voces Oral History Project at the University of Texas.

Gabaldon received many honors besides the movie. He gave countless talks to veterans, children and students, and was handed the keys to Osaka, Japan, considering that his performance actually saved many lives in that country.

The brave soldier died in 2007 without seeing his Medal of Honor.

“I don’t deserve the Medal of Honor, I enjoyed what I was doing,” he told his interviewer. “Medals of Honor should be awarded posthumously.”

So, maybe it is about time now.

Download The Daily Chela TV App

Download the new Daily Chela TV app on Apple IOS, Android, or Roku.