There are dead that cannot rest, because when they were alive their presence was too strong.

Last year marked the 100th anniversary of Emiliano Zapata’s death. Zapata, the man from the mountains of southern Mexico, fought for land, freedom and justice for the “peasants.”

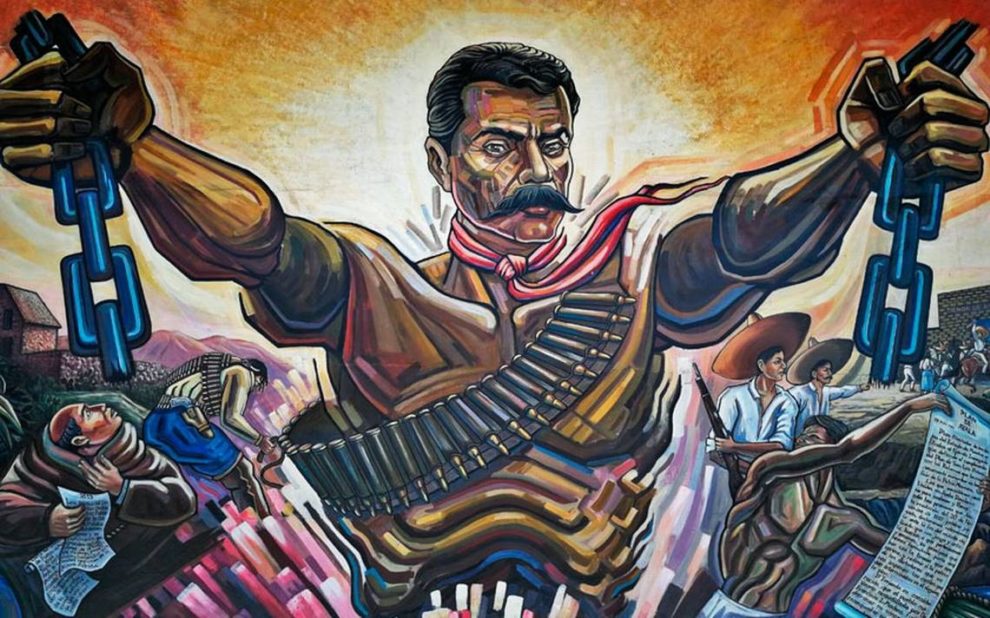

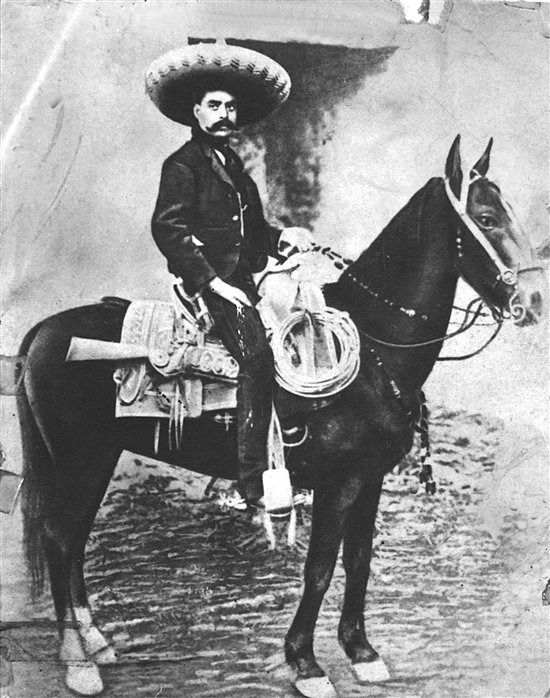

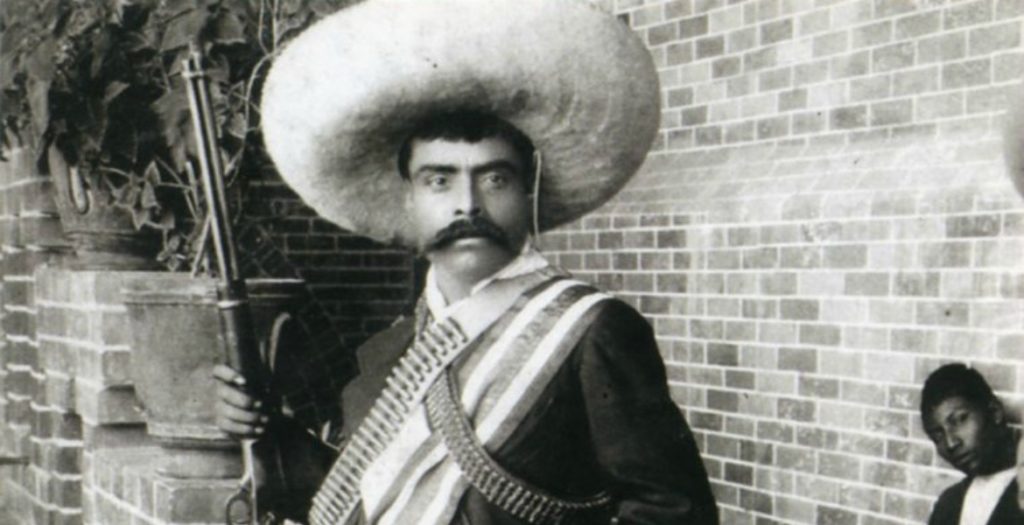

With his huge sombrero, his serious, tanned face with attractive features, his rifle and charro suit, for years his image was the ideal prototype of the Mexican man.

The golden age of Mexican cinema is replete with characters that look like him.

What not everyone has agreed on is Zapata’s soul. What defined him? In life, dirty politics and name-calling followed him as tenaciously as the enemy armies.

Last year, on the centenary of his death, he was haunted by another image, a kind of reverse of the coin.

In an artistic exhibition organized by the Mexican Secretariat of Culture, a small painting showed a feminized Zapata, like a minotaur, with half a woman’s body and half a man´s, high heels and a pin-up pose reminiscent of the 1950s.

In another context, no one would have paid attention to the work. In fact, it had already been exhibited without trouble or fanfare, but the Government chose it to promote the exhibition at the Palace of Fine Arts, and tempers were heated.

Many Mexicans felt offended. Some demonstrators forcibly closed the Palace and demanded that the work be removed.

In a time especially sensitive to these issues, the clashes between those who thought that Zapata’s image had been desecrated and those who were reacting to the apparent homophobia of the protesters, soon came to blows.

Attila Of The South

The controversy over the feminized Zapata painting—an otherwise irrelevant and artistically dull work—is the continuation of a series of interpretations that have followed Zapata since he was alive.

In the midst of the Mexican Revolution, the newspapers baptized him as the “Attila of the south,” for his alleged ferocity, and accused him of raping women, having a harem and committing all kinds of monstrosities.

“I do not recognize any government except the rule of my pistols,” he supposedly said.

In 1911, the president of Mexico, León de la Barra, who referred to Zapata as “the bandit,” announced that he would send the army to seize the peasant leader.

Zapata was nearly captured. He escaped through the back door of a hacienda where he was hiding and for a time he wandered the mountains on a donkey, barely surviving. But like a magnet, the peasants began to follow him until they formed an army.

“The important thing is to think with Zapata, not about Zapata.”

In 1912, The North American Review wrote about the situation in Mexico: “In various parts of the country there were disorderly bands of armed men committing numerous depredations.

Of these brigands—for they were nor more nor less, whatever they may have called themselves or may call themselves now—the most formidable was Emiliano Zapata.”

A Passion For Justice

Emiliano Zapata was not a saint, but in his situation who can be? When the next president, Francisco Madero, tried to negotiate with him, Zapata argued that his patience had run out because the lands had not been returned to their rightful owners, the peasants.

When the envoys asked him what answer they should bring to the president, Zapata replied: “Tell him that his days are counted. In a month I will be in Mexico City with twenty thousand men and I will have the pleasure of reaching Chapultepec (the presidential residence) and I will take him out and hang him from one of the tallest trees”.

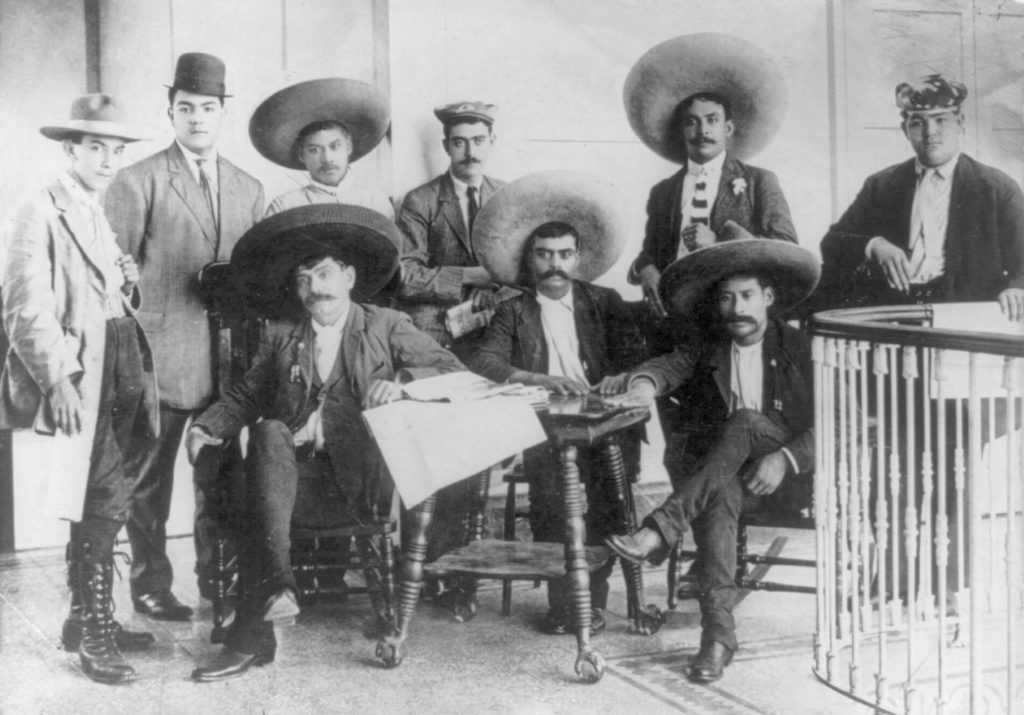

Despite having a price on his head, Zapata was an international celebrity. At the beginning of 1916, Guillermo Ojara interviewed him for the newspaper El Demócrata.

After many hardships, the journalist found the legendary caudillo “dressed simply in a plain black suit, but with large diamond on both hands and a heavy gold watch chain running across his breast, and his belt filled with cartridges and an automatic pistol slung at either hip. Zapata turned toward me, the inexpressive face of an Indian of about 50 years of age (he was 37) with remarkably penetrating eyes.”

The New York Times was sadistic: “Zapata seems to belong to another century,” the paper published in 1919. “Savage, boastful, fond of loading his person with diamonds and gold, polygamous, a patriarch of banditry, he fulfills the book-and-boy idea of a robber.”

The Ghost Of Zapata

Zapata was killed treacherously by a colonel named Jesús Guajardo, a government agent, in 1919. At the news, almost all of the Mexican newspapers praised the Lord. After his death, Zapata was like a well where everyone saw the reflection they wanted.

Recognizing that his name was stronger than the tomb, the same government that betrayed him raised him to civic altars.

Yet others believed that he had justly deserved his fate. When a film about his life was released in 1970, José Juan Guajardo, the brother of Zapata’s assassin, threatened to kill actor Antonio Aguilar because the film defamed his brother.

“Zapata was a bandit,” Guajardo said in 1974. “If the law does not punish him, I myself will execute Antonio Aguilar. I have the guts to do that and much more.”

One of the top military men of Mexican´s government reacted differently to the movie: “And when the f**k was that son of his f**ing mother a General? That bastard was a coward and he was always on the run!”

Twenty-five years after the events, the indigenous people of southern Mexico rebelled in his name and formed the first Zapatista army to be named like that since the hero’s death.

In this century, a novelist, a filmmaker and an artist have suggested or affirmed that Zapata was gay, although according to the painter of the Palace exhibition, he was not trying to make a statement about the historical Zapata, but about the glorification of the macho. It is only the continuation of what someone once called the “battle for the soul of Emiliano Zapata.”

However his figure can be reinterpreted, what really matters is to remember that Emiliano, the historical man, was first of all about social justice.

In the words of one of his biographers, Samuel Brunk, the important thing is to think with Zapata, not about Zapata.

Download The Daily Chela TV App

Download the new Daily Chela TV app on Apple IOS, Android, or Roku.