In the beginning, it was a vague idea, the approximate and inhospitable edge of the Spanish Empire and the beginning of no man’s land.

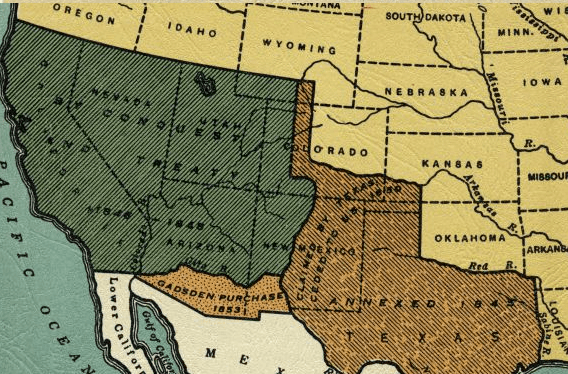

At the end of the 18th century, the primitive United States of America was far from the nation that would soon become Mexico. Even more “recently,” in the middle of the 19th century, the border between Mexico and the States was only a line drawn on a piece of paper, a porous boundary with no man-made barriers.

Mexico was officially born at the end of 1821. So for two centuries now, along two thousand miles, Mexicans and Americans have had a bittersweet neighborhood.

How The Line Came To Be

The line from San Diego/Tijuana to Brownsville/Matamoros is as large as Western Europe. It measures just about 2 thousand miles from the Pacific Ocean to the Gulf of Mexico, a distance equivalent from Madrid to Warsaw. It passes through fertile valleys, white deserts resembling the Sahara, mountainous areas and wetlands. It has a culture of its own and even, in the opinion of some linguists, an incipient language, Spanglish.

The border of the United States and Mexico is its own country.

The first physical demarcation of the frontier by the International Boundary Commission wasn’t solid at all: after the Mexican War (1846-1848) the team built a series of 276 obelisks—which remain to this day—every few miles from El Paso to the twin cities of Tijuana and San Diego.

The obelisks, about two meters high, still stand as mute witnesses of that first physical demarcation. Some are in urban areas, others in private farms, some in more inhospitable regions and others on the top of the highest mountains.

A Small Exodus

The first great migration between the two countries went from north to south. With the defeat of the Confederate States, thousands of refugees and defeated troops fled into Mexico in sufficient numbers to alarm both the triumphant Union and the Juarez republican government. But Mexico’s Maximilian Imperial Government was pleased to see the flow of what he considered diligent workers and loyal supporters of his Empire.

In the last week of the American Civil War, 10,000 men crossed the Rio Grande into Mexico, some of them with their families, determined to begin a new life. Imperial officers at the borderline let the refugees cross the border at several points without bothering them.

It is not clear how many Southerners finally arrived in Mexico. Some may have assimilated into their new country, but most of them probably returned to the States once Maximilian’s Empire crumbled down in 1867.

Once their respective internal wars were over, the neighbors observed each other again: Mexicans witnessed how the North began its reconstruction with fractured infrastructure, and a divided and resentful population. The Americans eagle-eyed the consolidation of a southern nation that had passed through half a century of revolutions, finally reaching stability with the arrival of president Porfirio Diaz.

The Second Great Migration

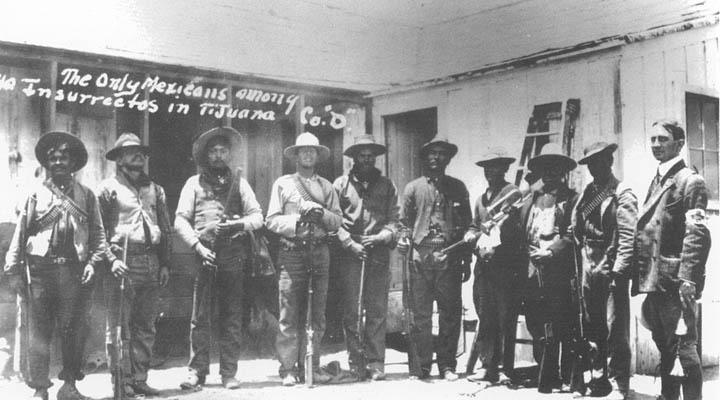

At the beginning of the 20th century, there were still no fences, no signs, except for the obelisks planted in 1851. Mexicans could freely cross the border without anyone stopping them, the same for the Americans going south.

At last, after many attempts, the occupation of the desolate northern territories began, accompanied by a beneficial exchange for both sides. In 1889, the city of Tijuana was founded with a purely tourist vocation: to entertain Californians who crossed in search of what they saw as a decadent culture of leisure and recreation.

In 1903, the twin cities of Mexicali and Calexico were created. Ciudad Juárez, which had existed since 1659 as “El Paso del Norte,” became the most important border city during the Diaz administration.

For many years, Mexicans swam across the Rio Grande unmolested or walked through the deserts of New Mexico and California. That relative informality of almost half a century changed at the beginning of the Mexican Revolution in 1910.

An Early Mass Deportation

But even then, the controls were still far from rigorous: the only requirement to cross the border was to identify and take a bath to “get disinfected.” In 1917, a new immigration law required Mexicans to prove they were literate.

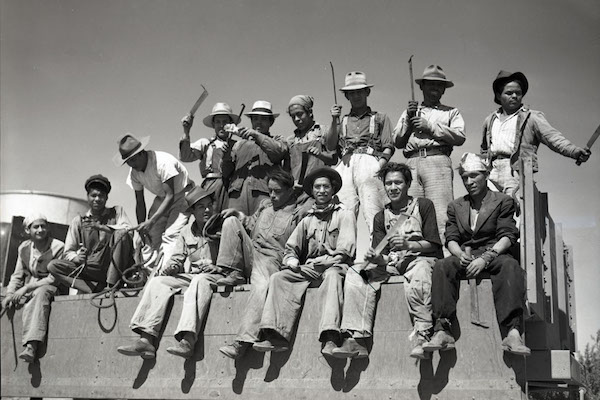

More importantly, the United States needed all these people: the beginning of World War I brought a dramatic decline in European immigration, the ban on immigration from Asia, and thus an impressive increase in labor demand, which the Mexicans fulfilled.

The trend suffered a severe setback in the 1930s, the Great Depression reduced the demand for Mexican workers to zero and a policy of mass deportation was implemented for the first time. During the 1930s between half a million and one million Mexicans and their American-born children were deported.

The “Bracero” Era

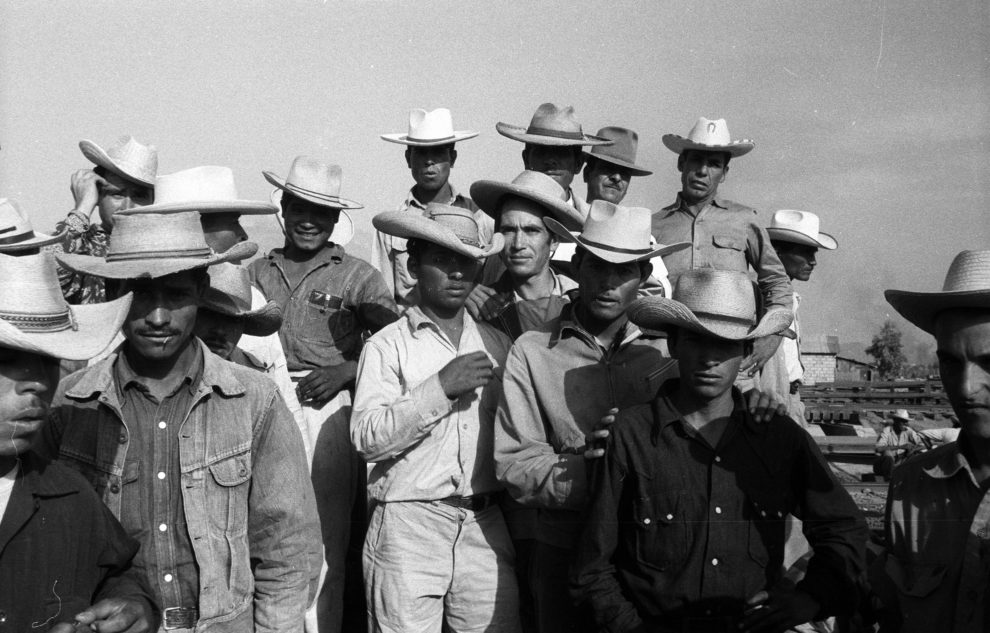

In 1942, the US went from mass deportation to official request of Mexican workers. With World War II, the army and the fields demanded more personnel, and the farms required men to replace the lost arms.

California farmers voiced their concern that there would be a shortage of labor for the harvest of 1942 and they requested the US government to bring in 100,000 Mexican workers.

This was the beginning of the Bracero Program.

In the first year, 4,200 full-service Mexican workers entered the states. Three years later the number increased to 62,000. But the program was too beneficial for the economy of the American farmers, who demanded that it continued for a few more years. In 1956 the number of legal “braceros” reached a historical maximum of 450,000 migrant workers, until it was finally canceled in 1964.

The Third Wave

The current situation began with the end of the long period of stability and growth in Mexico, an era known as “stabilizing development.” The “third major wave” of migration, again from south to north, began in the mid-70’s and continues to this day. It was the onset of one of the largest continuous migratory flows in the history of the United States.

In the 21st century the border has urgent issues: environmental pollution, water, crime, gangs and drugs, poverty, public health and safety, education and inadequate infrastructure, to name a few.

Today, the three central issues that dominate the U.S.-Mexico relationship are drugs, immigration, and security. Author Timothy Brown has imaginatively pictured the border as “schizoid set of Siamese twins physically joined at a hundred points and unable to survive apart.”

Only in this case, the treatment is not the surgical separation of the twins, but following that old adage: neighbors by chance, friends by choice.

Please Consider Becoming A Subscriber

We have made tremendous strides since we first launched last year, but we can’t keep growing without your support. Please consider becoming a Daily Chela subscriber and supporting our work. Choose from our different plans here.