They call her “Santa Muerte,” and the name means Good Death or Holy Death. The term was borrowed from Catholic prayers asking for a peaceful demise from this word, in peace with God, satisfied with life. The medical nation has its own word for it. The Greek word is euthanasia, which also means “good death,” the right to die without unnecessary suffering.

Be it good or holy, the concept is not new.

Since the beginning of the 21st century, a bizarre cult has grown from a solitary street altar in a poor neighborhood in Mexico City to a continental phenomenon which is now studied by scholars. It is the Santa Muerte cult.

Perhaps its more original feature is that, while in Catholicism the good/holy death is a process, and in medicine is a procedure, the cult of Santa Muerte turned it into a person.

Its acolytes say that deep down it’s the same thing: the desire to have a death without physical pain, the hope to experience a peaceful demise.

But since in this new movement Death is a person, a third element must be added: the desire, the obligation among her followers, to please and worship her (in Spanish the word death is a feminine noun).

Her devotees call her loving names: beautiful one, skinny woman, cute girl, little mother, and even virgin.

21st Century Remix

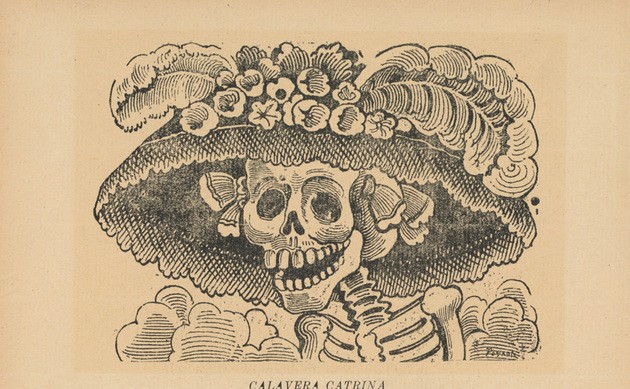

A few scholars claim that the Santa Muerte is a direct descendant of the Aztec deities of death, but she is not a symbol of fertility and abundance. And she is not a direct descendant either of the mexicanísima Catrina, like others presume.

“Santa Muerte is now a massive global business involving the chain production of statues in two continents, movie deals, book presentations, juicy contracts in the building industry (temples and planned cathedrals) and copyright battles.”

Unlike The Catrina, made by the early 20th century artist José Guadalupe Posada, Santa Muerte is not interested in social criticism or mocking the hypocrisy of the middle class. It doesn’t matter how much scholars want to establish a line of continuity (and thus some legitimacy) between the pre-Hispanic gods of death, Posada’s Catrina, and the Santa Muerte. The “white lady” is a modern concept.

Discovered By An American

The first reference to the modern cult of Santa Muerte appears in a novel by American anthropologist Oscar Lewis, Los hijos de Sánchez. Lewis published his story of a Mexican family in 1961.

Martha, one of the characters, says: “My sister Antonia (…) told me that when husbands are straying, you can pray to the Santa Muerte. It is a novena that should be prayed at twelve o’clock.”

Originally, the Santa Muerte was the one to go to rehabilitate unfaithful husbands.

Lewis published his work at the beginning of the 60s, meaning that the cult existed at least since the mid-50s in the Tepito neighborhood in Mexico City. In Lewis’s novel, the novena to the Santa Muerte is treated like a secret, passed by word of mouth among women.

Birth To The World

The cult stayed underground during the whole second half of the 20th century until it exploded at the very beginning of the 21st.

In 2001, on Halloween day, a woman named Enriqueta Romero, who until then had made her income selling quesadillas, put an altar to the Santa Muerte outside her house, on Alfareros street, in Tepito, the same neighborhood where Sánchez located his novel.

Mrs. Romero opened a small shop with souvenirs: books, medals, pictures and candles of the Holy Death. It was a roaring success.

The cult didn’t go unnoticed to Hollywood. In 2004 there was a brief mention in Man on Fire, a film starring Denzel Washington. But it was in 2010 when the American public had its first massive exposure to the icon thanks to two popular TV series: Breaking Bad and Criminal Minds.

What Do They Believe?

If the Santa Muerte is a person, then who is she, according to her worshippers and followers?

The Holy Death started as a character with the ability to grant any miracle, regardless of its moral value: it could be recovering a lost lover, getting a job, or protection while killing an enemy.

But the central expectation is to obtain protection and shelter, in a world of abandonment and insecurity, and to experience a good, painless death.

Her identity is a matter of debate. Some followers theorize that she is an archangel. Others see her as a demigod, who controls the lives of all beings in the universe. Some others believe that the Santa Muerte is a soul from purgatory. Finally, there are those who see her as a demon.

Reaction

Esequiel Sánchez, a well-known Catholic minister, expressed his concern in 2008, when some parishioners asked him to bless their statues of Santa Muerte.

“I’m concerned about it because it’s an aberration. It’s a misunderstanding of faith. At the same time, I can understand why it’s growing. Many people, especially Mexican immigrants, are feeling that institutions are abandoning them.”

Large-scale opposition has come from the Mexican government. The antagonism grew when its intelligence forces started noticing the relationship between drug trafficking and appearance of altars on highways; between ritual murders, violence and growth of worship. Scholars also found that the cult flourished in those areas of the city where families had had members in prison.

Needless to say, not everyone who follows the Santa Muerte is involved in the organized crime —there are many sincere believers, as there are in Santería and the New Age movements—but the link between the cult and narcotrafficking, while it may not be causal, is firm.

A New Religion Or A New Business?

And there are of course more mundane reasons to explain the cult’s success: business opportunities. Santa Muerte is now a “global business (that) ranges from the mass production of statues in China and Mexico, to a Salvadoran seamstress working out of her Los Angeles home, making $1,000 dresses to order for Santa Muerte statues,” wrote Ana Facio-Krajcer for The Washington Post.

Thus, rather than a romantic and ancient cult of the dispossessed, the Santa Muerte is now a massive global business involving the chain production of statues in two continents, movie deals, book presentations, juicy contracts in the building industry (temples and planned cathedrals) and copyright battles.

A Saint For A Terrified Mexico

But its origins are worth an explanation. The Santa Muerte is perhaps an emotional reaction in a country terrified by death and violence, therefore the people’s need to give her an identity and to keep the Grim Reaper happy, a kind of Stockholm syndrome. Posada personified death too, with a different purpose.

However, death was always supposed to be a metaphor. José Guadalupe Posada carved his famous Catrina to mock those taking the upper class too seriously, but he knew that the skeleton was always a metaphor, same for the Aztecs for whom it represented cosmic forces.

Perhaps it would be more uncomfortable, for those who are violent, if the people started asking what the symbol means and why it became a person, rather than take it literally.

Please Consider Becoming A Subscriber

We have made tremendous strides since we first launched last year, but we can’t keep growing without your support. Please consider supporting our work by becoming a Daily Chela subscriber. Thank you!