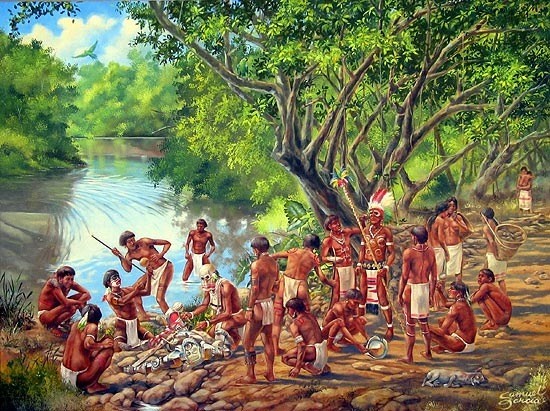

One can imagine how striking the island that was later called Hispaniola was when they first landed on its shores. With breathtaking seascapes, majestic palm trees, and lush mountains, it wasn’t surprising that there were already people enjoying its fruits.

We don’t know the name of these people, but we know that when the Taíno first encountered them around 400 BC, their approach was much different from that of Columbus. That is, they did not enslave and subjugate them. Not much is known about these indigenous people whom the Taíno would eventually overshadow. More is known about the Taíno, despite the Spanish-sponsored efforts of Columbus to wipe them out. The Taíno never died.

How Indigenous People’s Day Came to Be

Indigenous Peoples’ Day first gained federal recognition in 2021 under the Biden administration after decades of Native American activism. Columbus Day is still on the books, however, even though its origins are dubious.

Columbus Day was never an organic holiday. Its origins are rooted in the U.S.’s history of complicated relationships with any group that wasn’t WASP (White Anglo-Saxon Protestants). The late 1800s and early 1900s saw a wave of eastern and southern European immigration to the U.S., with those immigrants differing from the Anglo population not only in cultural terms, but also in terms of their Catholic and Jewish religions. As such, racism against these groups was rampant.

Tensions ignited in late 1800s New Orleans, with a mob attacking and killing Italians after the police chief there was killed, resulting in one of our nation’s most brutal lynchings. With the intention of calming the animosity between the nation of Italy and the U.S., Discovery Day came on the books in 1892, and officially became Columbus Day under Franklin D Roosevelt’s administration in the 1930s.

Columbus Day, then, was the consequence of a chain events—anti-immigrant racism and terror, followed by outrage on the part of immigrants and a desire for them to be seen as Americans, and then finally a prototypically pragmatic response by U.S. politicians to cool the fires of racial tension and appease Italy as a nation as well as its immigrants.

But Columbus Day isn’t representative of Italians’ contribution to America. Even the premise of assimilation is suspect; a group of immigrants should not have had to prove that they were worthy of being treated with dignity in the U.S. by appealing to the acts of a 15th-century explorer who just so happened to originate from the same peninsula hundreds of years before.

Plus, as brutally-lovable Sopranos enforcer Furio Giunta explained in the “Christopher” episode, Columbus was Genovese. That’s northern Italian, much different culturally and ethnically than the immigrants who made their way from southern Italian regions such as Naples, Calabria, and Sicily.

To this day, Italians tend to denote their origins by describing their family’s region—e.g., someone from Calabria will say they’re Calabrese before saying they’re Italian, and someone from Ischia will say they’re Ischian. Not to mention the fact that in Columbus’s day there was no unified Italy, with unification only happening in the late 19th century. Consequently, Columbus Day has a dubious relationship with Italians, a group that achieved greatness and made America better without Columbus having anything to do with it.

Colonial Savagery

That Columbus was a goon shouldn’t be controversial. But whether he was more of a goon than the other colonists is still up for debate. When he and the Spanish first set eyes on Hispaniola, they were happy to be able to subjugate and enslave the Taíno natives in pursuit of wealth. Spanish priest Bartoleme de las Casas famously made it his mission to call out the brutality of Columbus and the Spanish colonists, highlighting their hypocrisy in trying to to spread Christianity while forcing the Taíno to work in mines and mutilating and raping them without hesitation.

The story of Columbus is more complicated than many narratives suggest, however. There are accounts of him trying to curtail colonial brutality, and stories that suggest that his arrest and subsequent fall from grace was politically motivated. This is made even more complicated by the fact that de las Casas himself called Columbus a “good and Christian man.”

But the fact remains that the Taíno were treated brutally, and Columbus did participate in this brutality. Now, in their colonial milieu, this brutality was acceptable, which is demonstrated by de las Casas’s calls for an end to the colonial savagery going unheeded. De las Casas was not unique in his moral firmament– Columbus and those who colonized the Caribbean were Christians and thus had a firm understanding that murder and subjugation were moral wrongs. And yet the system incentivized their callous treatment of the Taíno and other native groups.

Thus, the rejection of Columbus Day isn’t a rejection of Columbus as a uniquely psychopathic conqueror with an insatiable appetite for depravity—he wasn’t—but instead a rejection of the celebrations that whitewash systemic colonial depravity and the uplifting of the cultures that endured such horrors. Because against all odds, those cultures endured.

How the Taíno Live On

Christopher Columbus died; the Taíno people didn’t. Long after their numbers dwindled due to colonial savagery and disease, the Taíno survived, having mixed with Africans and Spanish on the islands. The Smithsonian Magazine reports studies having found that a significant percentage of the Dominican and Puerto Rican population have indigenous DNA as a result of the Taíno people.

Their influence lives on not only in Puerto Rico and the Dominican Republic, but also in language and food. Words such as barbecue, hammock, hurricane, tobacco, and canoe are all derived from the Taíno language and still in use today. Food like cassava, made from yucca, is still in widespread use and is a fundamental ingredient in the flatbread called casabe. Other foods include the perennial nourishment that are black beans, sweet potatoes, and plantains, among others.

That’s not all, though. The Taíno influence can be felt in dishes like the Puerto Rican pastel—a culinary cousin of the Mexican tamale—and even in the legendary dish of mofongo, according to the Smithsonian magazine. Some even claim that the Taíno helped influence Jamaican cuisine in the form of its jerk cooking.

All of this matters because food, culture, and language are how a people survive, and adds an unquantifiable richness to the human experience. Now that indigenous peoples are receiving their due, there’s greater awareness of the people whose stories have been ignored by the mainstream media for generations.

What indigenous groups like the Taíno have overcome is, in a way, much more worth celebrating than the actions of one man who bears no cultural imprint on the islands or on the broader Americas. We celebrate Indigenous Peoples’ Day because they are the victors; we will enjoy their spoils.

Please Subscribe To The Daily Chela To Show Your Support

The Daily Chela is a new Chicano/Latino digital news organization. It has been cited by NBC News, Yahoo News, Vox, The Washington Post, Fox Sports, former presidential candidate Julián Castro, and the National Association Of Hispanic Journalists. Please consider subscribing and showing your support.