The Ghost Of Christmas Past

According to an old Colonial document, it was a man named Pieter van der Moere (better known to history as Fray Pedro de Gante) who first celebrated Christmas in Mexico. It was December 25 when the friar, born in present-day Belgium, gathered a crowd of Indians and taught them to sing “The Redeemer of the World is Born.” This took place in the early 16th century, somewhere in Mexico City.

That was the first Mexican Christmas.

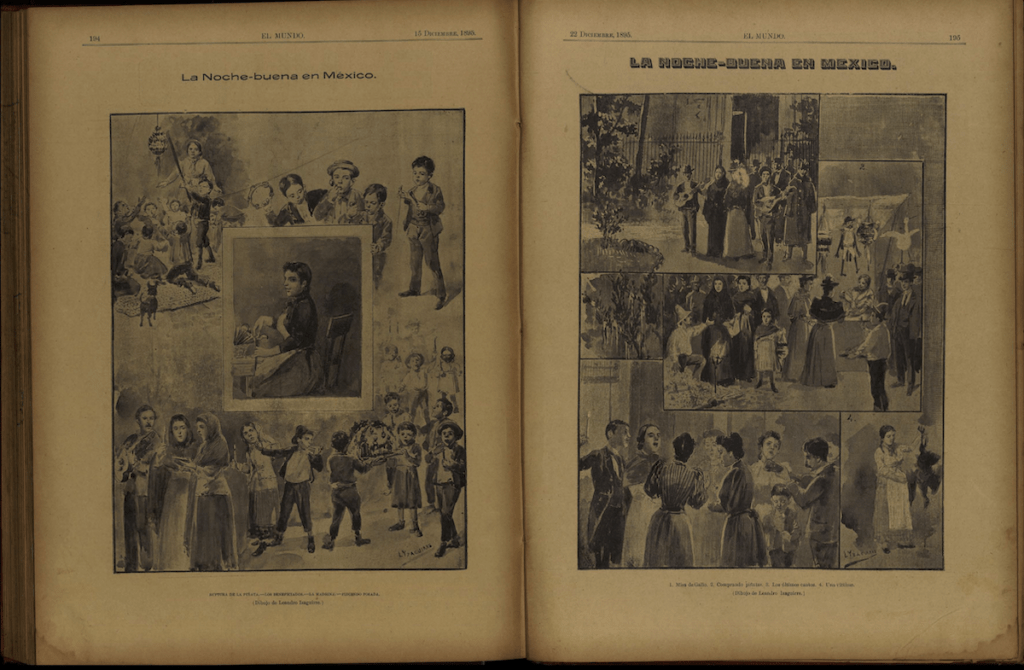

The universally famous piñata was also born in the 16th century, when the friars began to celebrate the “posadas” during the days leading up to Christmas. The piñata was then used as a visually attractive and collaborative allegory (where action was needed from the observers) to evangelize the inhabitants of the region.

In the following two hundred years, in a slow process, the Christmas traditions that became recognized as “eminently Mexican” took shape and local flavor: the posadas, the Nacimiento, the pastorelas, the Mexican piñata and its children’s canticles (I don’t want gold and I don’t want silver, I just want to break the piñata).

Some of them were, of course, adopted via Spain. They moved from the essentially religious (Catholic) realm to become a semblance of the people who adopted, transformed and cherished them as part of their Mexican identity. This included the families that moved abroad and took them to Los Angeles, Chicago or San Antonio.

How did our ancestors celebrate Christmas? Historical sources offer interesting descriptions. For example, a Mexican newspaper from 1877 describes the celebration in the main plaza of Mexico City as the following:

A combination of dogs howling, boys screaming, voices of merchants offering their products. A strong smell of mango, pine branches and burning wood overwhelms the nose. A crowd of men, women and children crowd in front of a thousand small wooden shops look for the essential objects for the last Posada: moss to form a mountain, silver thread to imitate the snows of Palestine, shepherds’ huts, figures of clay animals, candles of all colors and mountains of sweets. And the crowd becomes agitated, and disputes with the vendors, and buys one a pint of peanuts from one, and two pounds of candies from another, and a dozen stars at the other side.

Anyone who grew up in a Mexican family, even in the 70s and 80s, knows that these sights, sounds, and colors were still commonplace a few decades ago.

In 1885, another Mexican newspaper described the decoration of a Christmas tree—something very foreign and exotic at the time—and recommended it to its readers as a harmless pastime:

“The custom of the Christmas tree has been introduced by Europeans, mainly Germans, English and Swiss. A small tree is placed in the living room of the house or the banquet table, loaded with various curious objects for the amusement of the children and guests. After Christmas day the children are invited to another meeting to receive the objects of said tree.”

In 1897 another source tells us how in Mexico “the Church ceremonies, always severe and majestic, become joyful and, so to speak, boisterous. All the noise that a hundred little children can make with drums and whistles is admitted in the temples, instead of solemn music, and the organ plays sonatas and harmonies.”

The Ghost Of Christmas Present

So when did Christmas stop being “Mexican” and begin to look more like average winter celebrations, with Santa instead of the Three Wise Kings, and American carols by Luis Miguel instead of the Posada litany?

It is true, for the nostalgic there will always be something amiss. Already at the beginning of the 20th century, the great geographer Antonio García Cubas lamented how winter traditions were being lost in Mexico.

But it was especially with the commercial and cultural opening of Mexico in the last decades of the 20th century that the celebration began to take on another air. Yes, Mexico is located in the northern hemisphere, and Christmas falls in winter, but most of the country is desert or semi-desert. The imagery that the Western world associates with the holiday was alien in Mexico for centuries.

Now visit a big mall in Mexico in 2022 this Christmas and it will feel like you are north of the 40th parallel: snowy landscapes, reindeers and pine trees. Artificial, of course. Monotonous muzak comes from loudspeakers in shopping malls, banks and restaurants with songs about sleigh rides and reindeers (a non-existent animal in Mexico), even in Monterrey, where temperatures in December can reach 85 F degrees.

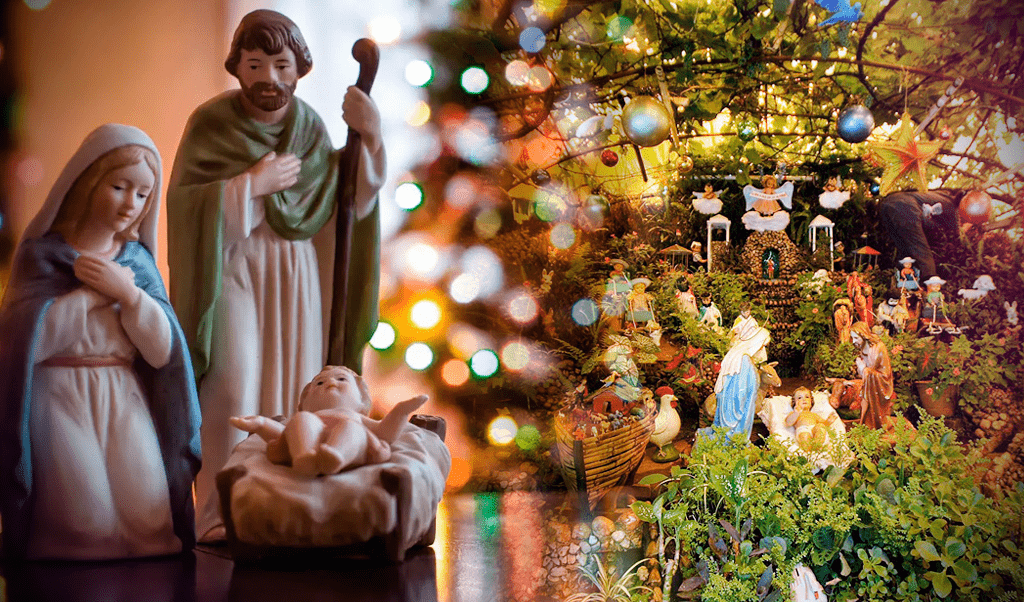

The historic traditions dissipated in the face of modernity and secularization. Now “posada” is only an umbrella word to designate any meeting among friends in the weeks before Christmas. The nativity scenes or Nacimientos, that required family time to set up have practically disappeared, except in small towns, and they have been replaced by a pine tree with a greeting in English at the top.

Finally, pastorelas were supplanted by fancy concerts with the music of The Nutcracker, by Russian composer Pyotr Tchaikovsky.

Political Correctness and The Ghost Of Christmas Future

It is true, some features of those historical Christmas survive in rural places and popular neighborhoods, both in Mexico and the United States among the Latino population. And in recent decades, the government, through its cultural institutions, has made an effort to keep some of those traditions alive for their cultural and artistic value.

But this valiant effort may disappear too. It is not only the passage of time and oblivion that is changing Christmas in Mexico, but also political correctness. During the month of November 2022, the Supreme Court of Justice of the Nation discussed an amparo appeal to put a ban on the public display of Nacimientos.

A civil organization in Chocholá, Yucatan, sued the municipal government for placing a Nacimiento on public display —the plaintiffs considered that the nativity scene violated their freedom of conscience and tried to impose on them values they did not share.

If ruled favorably, the resolution by the Supreme Court to ban the Municipality of Chocholá from placing any symbol referring to the birth of Jesus Christ could lead the way to a ban in the rest of the country, and by the same logic, on Pastorelas (since they are, in a way, street religious processions) and state-sponsored Christmas concerts.

Who knows, maybe even Tchaikovsky’s Nutcracker will have to go!

A Roundup Of Mexican Christmas Traditions

Misa de Gallo. This is celebrated on the night of December 24th. Literally “Rooster’s Mass,” people attended at midnight right before the family dinner, although in the 19th century the mass was celebrated in the early hours of dawn, hence its name, because it was like the rooster that announces the arrival of dawn.

A common character in historical novels and plays in Mexico were men who attended this Misa de Gallo in a very inconvenient situation—drunk as a skunk.

Nacimientos. One of the favorite traditions of the Mexican family consisted of putting up the nativity scene or Bethlehem, with plants, clay figures, animals, shepherds, the three wise men and a small stable with the figures of Joseph and Mary. The whole family participated in decorating and changing the places of the figures every day so that they would not be static.

Today increasingly rare, big Nacimientos could be seen in many villages and neighborhoods in a visible place so that people would go to pray together.

Posadas. The Posada was the most distinctive element of the Mexican celebration, not one but nine, every night between December 16 and 24. They were street processions. People wandered from house to house singing, costumed like Mary, Joseph and shepherds.

They also chanted verses of undoubtedly antiquity, with candles in their hands, knocking on doors, until one house was opened and the Posada would begin. Then some blindfolded children would break the famous piñata singing a cautionary ditty of unknown antiquity: Hit it, hit it, hit it! Don’t lose your aim, for if you lose it, you’ll lose the way.

The Obispillo. Another Mexican tradition that has been completely lost to the extent that barely no one alive remembers it. The Obispillo, or “Little Bishop,” was a day when the children sat behind the altar of the temple as if they were priests, dressed in habits, while the real bishops and priests fulfilled the functions of altar boys, a role reversal that was performed on the days right after Christmas.

Download The Daily Chela TV App

Download the new Daily Chela TV app on Apple IOS, Android, or Roku.