With a renewed interest in Chicano culture and Chicano Studies courses, many Latinos are asking: What is the meaning of the word Chicano? What is the meaning of the word Latino?

So in this blog, I’m going to try to define and explain the following:

- A Latino

- A Chicano

- A Chicano vs Latino

Latino Meaning

A Latino is predominantly an American term used to refer to anybody who is of Latin American descent, meaning a country in the western hemisphere that speaks one of the Latin romance languages (Spanish, Portuguese, French, etc.). This includes dozens of nationalities, cultures, and ethnicities.

Alternatively, the Office of Management and Budget defines a Latino as, “a person of Cuban, Mexican, Puerto Rican, South or Central American, or other Spanish culture or origin, regardless of race.”

- 8 Old School Magazines That Chicanos Still Collect

- Aztlán Youth Brigade Advocates Chicano Empowerment In Barrio Logan

Over time, this term has come to replace the term “Hispanic” which only referred to countries that spoke Spanish, and excluded countries like Brazil.

In addition, the term “Hispanic” is a derivative of Hispania. As a result, it is frowned upon because of Spain’s colonization of the Americas.

Chicano Meaning

The late Chicano journalist Ruben Salazar once said, “a Chicano is a Mexican-American with a non-Anglo image of himself.”

Salazar wasn’t wrong. However, understanding the different subcultures within the larger umbrella of Chicano culture is equally important.

To be more specific, a Chicano is a Mexican American who identifies with either one of the social or political aspects of Chicano culture—or both.

Support Chicano/Latino Media. Subscribe For Only $1 Your First Month.

These sub-cultures are expansive and often overlap. As I wrote in a previous column:

“Chicano culture is a complex web of sub-cultures and movements. It is the Chicano Civil Rights Movement. It is the Chicano lowrider community. It is the Chicano art community. It is Chicano fashion. It is Chicano tattoos. It is pachuco sub-culture.”

Each of these subcultures can then be further broken down into additional subcultures.

How The Vietnam War Shaped The Chicano Movement

Few events played a bigger role in uniting the Mexican American community and strengthening the Chicano Civil Rights Movement than the Vietnam War, which “officially” began in 1955 (although an argument can probably be made it unofficially began long before that).

Mexican Americans not only served in the Vietnam War like white Americans, but like most Americans who were drafted and served, returned home to the United States after the war feeling defeated and disillusioned.

These feelings were only compounded over time following the war. On one hand, Mexican Americans felt forgotten about—their contributions left out of the classrooms and history books. On the other hand, their neighborhoods and families felt abandoned, left alone to pick up the pieces.

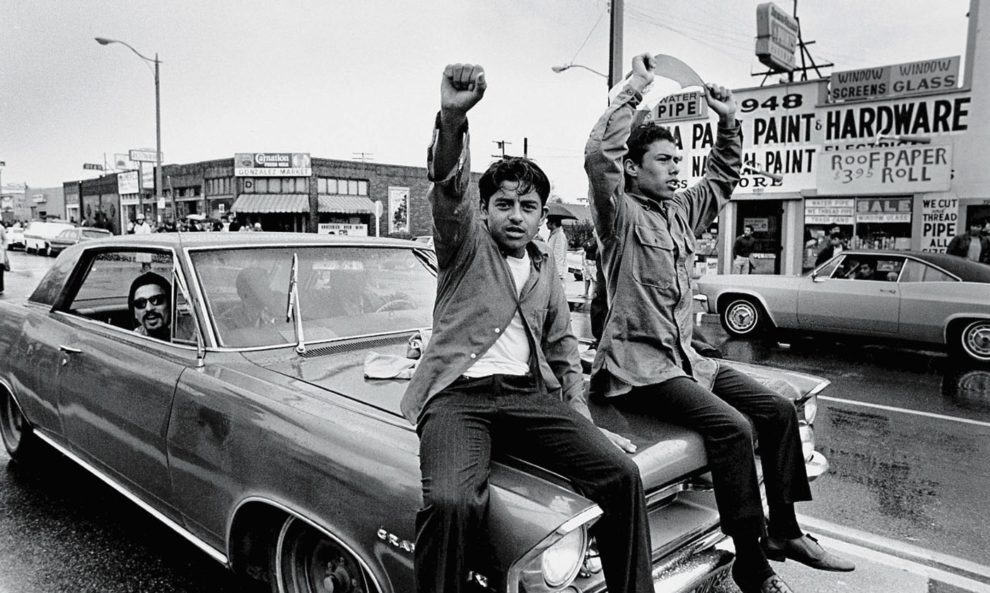

During the war, as young Chicanos waded through the waters of Vietnam, a loose coalition of anti-war Chicano groups emerged into what would become known as the Chicano Moratorium.

In one anti-war demonstration, activists drew upwards of 30,000 people to march through the streets of East L.A., further solidifying the power of the Chicano movement.

Chicano vs Latino

All Chicanos are Latinos, but not all Latinos are Chicanos. Chicanos are Mexican Americans who identity with one or more of the political or social aspects of Chicano culture, including the Chicano Civil Rights Movement (which includes numerous facets), Chicano art and tattoos, lowrider culture, Chicano fashion, or pachuco/cholo culture.

The irony of this is that the word “Chicano” initially began as an insult, only to be adopted and embraced.