Before Netflix and cell phones took over family leisure time, the Mexican public was one of the largest consumers of comic books in the world. Some researchers have calculated that, in the golden age, a Mexican family bought an average of six to seven new titles each week.

Many were imported from the United States—Spiderman, Donald Duck, Superman, etc.—but many were also highly original creations by Mexican artists and writers, earning Mexico a special place in the history of comic books. Mexico, after all, not only created great titles, but exported them to other Spanish-speaking nations.

The Origins

At the beginning of the 20th century, the El Buen Tono cigar factory produced a strip about a chain smoker named Ranilla. In 1919, the newspaper Heraldo de México published the first Sunday cartoon in color, which was called Don Catarino.

In 1934, Paquín debuted as the first Mexican comic that appeared weekly. Later in 1936, Chamaco became the first comic in the world to be published every day (that’s how high demand for comic books was!).

A golden age began in the 1940s and 1950s. But unlike the United States and Europe, the Mexican comic was mainly aimed at the popular classes. And while many titles were seen as “literary rubbish,” Mexican comic books helped educate the masses and spark the imagination.

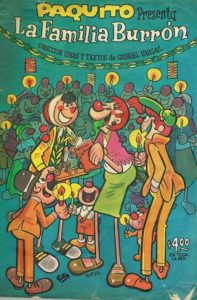

La familia Burrón (The Burrón Family)

Every person born into a Mexican family has heard about the Burrón Family, possibly the most famous and representative title in the Mexican pantheon. Created by Gabriel Vargas in the 1940s, it told the story of a family in a lower-class neighborhood in Mexico City.

At a time when comics with well-built and heroic men abounded, the heroine of this publication was a low-class woman named Borola Tacuche, who was intelligent, funny, and resourceful.

She was accompanied by a great cast who was always overcoming adversity. Each Mexican could see his or her own humorous reflection in one of the many characters that appeared in the magazine: the drunkard, the hard-working barber, the poet, the petty thief, the pretentious woman.

Mexican intellectual Carlos Monsiváis praised this comic, saying, “Borola and her neighbors, constantly fighting against market prices and empty pockets, generated a cartoon mythology of resistance… (La Familia Burrón) is a festive song about survival.”

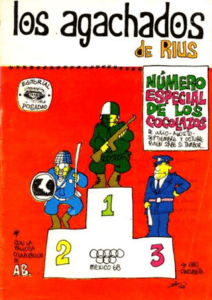

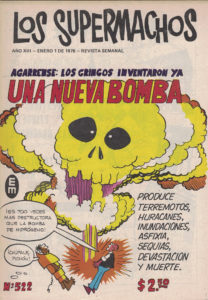

Los Supermachos and Los Agachados

“Rius,” whose real name was Eduardo del Río, was the pen name of one of the greatest Mexican cartoonists. His real name was Eduardo del Río, and he created several titles, not for children, but for adults.

Rius dealt with topics such as the Mexican political system, religion, the international monetary system, and the Cold War in his comics. If this seems boring, Rius’ genius managed to make it interesting.

In 1966, Los Supermachos appeared. Its characters, stereotypes of the Mexican citizen—the bureaucrat, the Indian, the idealist student, the sanctimonious woman—exposed thorny issues in an entertaining way. Rius was a lousy cartoonist (in his own words) but an excellent designer.

Los Supermachos and Los Agachados developed an amazing graphic style to deal with complex topics, and created a school which was copied around the world. Rius was highly controversial, and in the 1960s he suffered political persecution.

He was even tortured by the government.

Los Super-Sabios

Los Super-Sabios, whose golden age was from 1953 to 1962, did not enjoy the omnipresence of other titles, but its intelligence and the almost philosophical portrayal of characters made it a cult comic.

Its creator, Germán Butze, envisioned a series of science fiction adventures, where escapism and high imagination were the norm.

The main character was a boy named Panza. His grandfather beat him, but he always escaped, had adventures with scientists, and time traveled.

The characters had dark sides and often fell prey to intimate terrors. But that was also one of the achievements of the series, blending the world of adventure with the existential sadness of everyday life.

The philosopher Armando Bartra believed that “behind the escapist narrative, there is a poisonous family portrait with an oppressive social landscape. Without his bizarre escapades with Paco and Pepe, Panza’s life with her mother and grandfather would be an unbearable hell.”

Kalimán

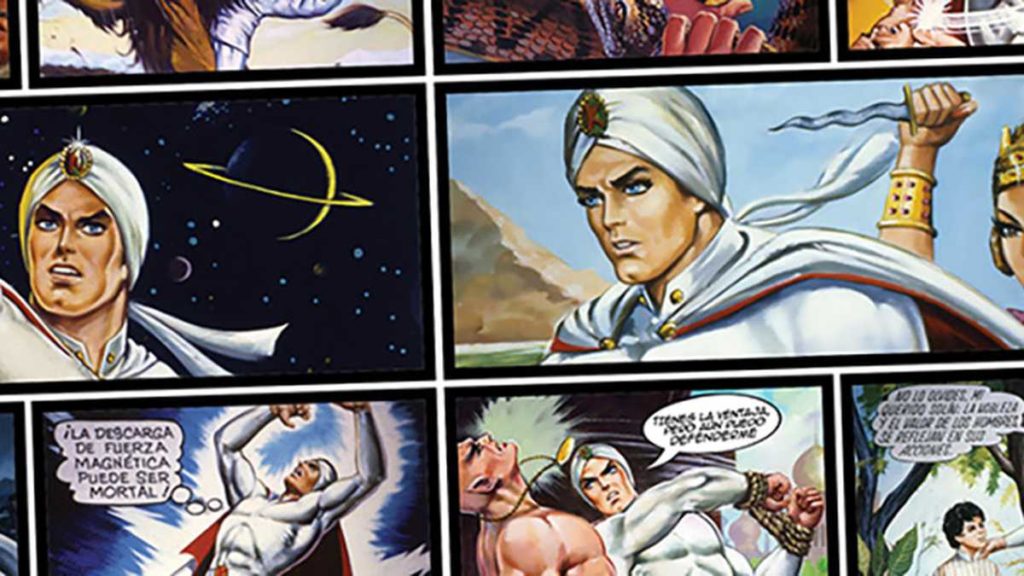

Kalimán is perhaps the greatest superhero created in Mexico. He was born on the radio in 1963 and jumped to his own comic book in 1965.

Kalimán also made it to the big screen on several occasions. He was the brainchild of two DJs, Modesto Vázquez and Rafael Cutberto Navarro. Kalimán, a very sui generis superhero, insisted on the supremacy of mind over force and was, if such a thing was possible, a pacifist.

Closer to Marvel’s Dr. Strange than to Superman, Kalimán sold one million copies a week in the 1970s, in a country with 10 million households. The comic book told the adventures of a man from India, educated in Tibet, where he acquired mental powers, such as hypnosis, astral travel, and a superhuman intelligence.

Kalimán spoke all the languages and was a walking encyclopedia. His recurring themes and teachings on spirituality, freedom, nature and human dignity, had didactic purposes for an audience eager for a form of entertainment that would leave them something once they closed the book. One of his favorite teachings: “Serenity and patience, especially a lot of serenity and a lot of patience.”

Lágrimas, Risas y Amor (Tears, Laughter and Love)

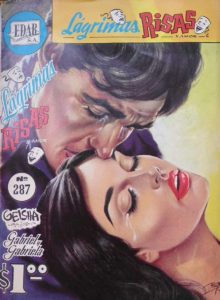

Mexican soap operas took the world by storm (notably Russia) in the 1970s and 1980s. But many of them originally appeared in a humble comic that was printed on sepia and cheap paper called Lágrimas y Risas, the creation of a woman called Yolanda Vargas Dulché. With no superheroes, funny characters or exciting adventures, the romance title was a massive hit among Mexican women.

The author proved that she was good at telling stories, as several of them became large-production TV soap operas, such as Gabriel y Gabriela, El pecado de Oyuki and Rubí.

In 1985, Yolanda Vargas Dulché signed her last tale, “Juan Valjean,” but her legacy did not die: almost all of her stories were adapted to the big screen and television as successful soap operas.

A New Generation

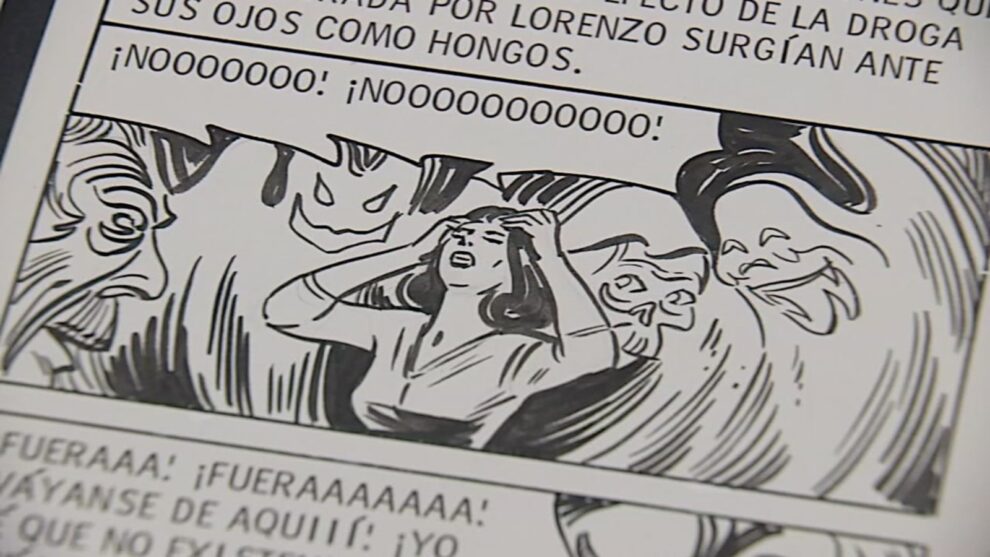

The golden era of Mexican comics began to fade in the 80s. The titles and authors gradually disappeared, leaving room for other lesser-known and flimsy publications, generic adventures about policemen, truck drivers, and cowboys, always accompanied by sexy women and sometimes sordid arguments.

The attention was not on comics anymore, but on re-emerging media such as cinema (entering now its silver age) and especially TV.

There were other efforts, educational comics such as Biographies of Great Men and adaptations of classic works, such as Les Miserables, and even graphic summaries of ancient works like The War of the Jews.

The Mexican government also produced a multi-volume history of Mexico called Historia de un pueblo, where many children (including this writer) became interested in history for the first time.

There were many more brilliant titles which are not mentioned here, including Memín Pinguín, Chanoc, Leyendas de la Colonia, Duda, Hermelinda Linda and others which new publishers tried to resurrect, but it was never the same.

The golden age of Mexican comics, for better or for worse, is now behind us.

Get Columns Like This In Your Inbox

To receive weekly updates like this in your inbox, subscribe to The Daily Chela newsletter here.