Steel doors crashed shut behind me as I stepped outside onto the curb. Sunshine splashed down onto the back of my neck. In nearly 2 months, I had lost 20 pounds, grown a full head of hair again, and gained a new appreciation for the virtues of solitude.

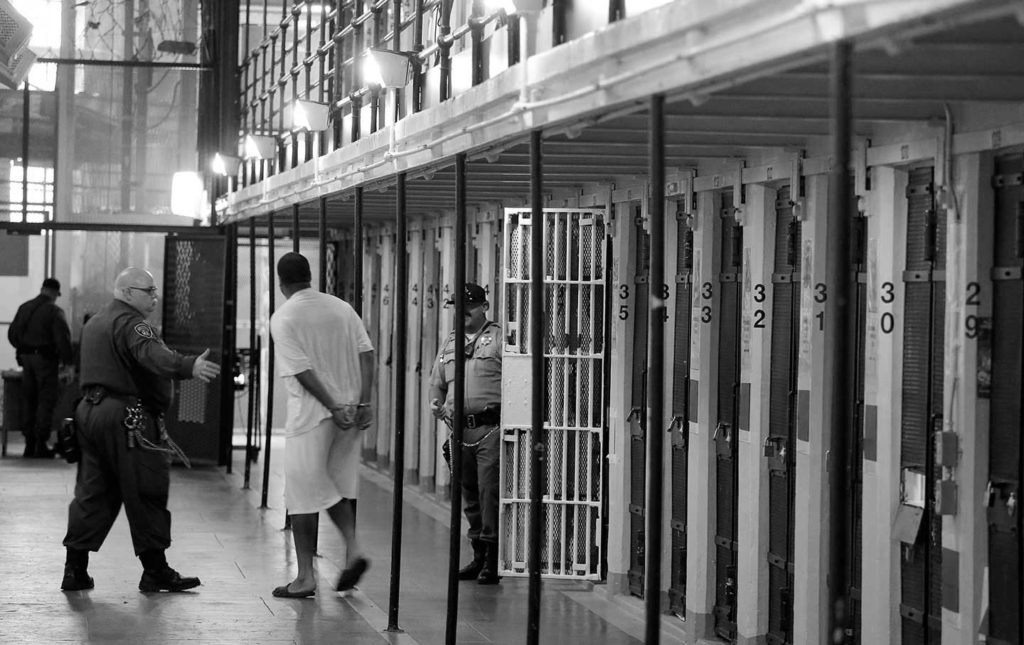

After all, when you’re a “violent offender,” 20 hours a day in a cell is the standard, not the exception.

The world felt different. Not because I had just navigated an invisible minefield that could explode at any moment. Or still felt strangely engulfed by the primal screams that reverberated across the cell block each night as I lay in bed—waiting to learn my fate. But because I had just glimpsed into the abyss of human despair. I had, in a desperate attempt to escape a five-year prison sentence, confessed to a version of a crime that never happened.

But at least I was free.

Little did I know that my true prison sentence was just beginning. Despite not owning a credit card, debt mounted from fines and fees. Despite having a stable work history, employers refused to hire me. And despite a clean rental history, apartments declined to rent to me.

The true reality of my situation sank in: While I could again feel a passing breeze on the back of my neck and till my fingers through the dirt on the ground, I wasn’t free at all. I was still very much a prisoner—hostage to a stigma.

Naturally, unanswered questions still linger in the back of my mind: How long should someone suffer for past indiscretions once their debt to society has been paid? How much discretion and power should district attorneys be trusted with at the expense of lives and tax dollars? Why don’t violent offenders, like drug offenders, also deserve a second chance?

Nation Of Prisoners

I’m not alone in my experience. The U.S. is currently home to more than 1.5 million state and federal prisoners, largely due to mandatory minimum sentencing laws. In addition, more than 4 million people are currently on parole or probation—a staggering statistic that means roughly 1 in 37 adults are in some phase of the criminal justice system.

But not all inmates are serving time for simple drug offenses or heinous crimes such as sexual assault and murder. Many are serving time for generic fights or assaults like I once was. And many will again have to reintegrate into society with a felony conviction like I once did.

Yet despite the fact that violent offenders comprise a substantial portion of the jail and prison population, prison reform advocates tend to disproportionately focus on “non-violent” drug offenders. After all, who wants to defend a gang member? A bank robber? A burglar?

I do. Because while taking up the cause of violent offenders might not be the most glamorous or popular thing to do, the truth is if prison reform advocates want to have an honest national discussion about rehabilitating offenders, eliminating mandatory minimum sentencing laws or reforming our prison system, then the discussion should include all offenders—not just drug offenders.

Mandatory Minimums

Few things have contributed to the nation’s bloated prison population more than handing district attorneys a blank check in the form of mandatory minimum sentencing laws with no oversight or recourse.

All too often, crimes are taken out of context. Worse, laws are abused or exploited by overzealous prosecutors who place personal status before justice. As a result, first-time offenders, many of whom cannot afford adequate representation, are coerced into choosing between unjust plea bargains or “all or nothing” trial scenarios.

Take my own case. I was hardly the first testosterone filled twenty-something-year-old male to ever get into a barroom scuffle with another inebriated male. Yet despite only throwing one punch in self-defense, the district attorney slapped me with numerous criminal charges, including “assault with a deadly weapon”—a mandatory minimum sentence crime that carried a five-year prison sentence.

There was just one problem: no weapon was ever used.

As I would come to discover, over-charging defendants is a common strategy called “stacking.” To get a conviction, prosecutors simply drown the defendant in a sea of bogus charges with sprinkles of truth and then dangle a plea bargain in front of them as a life jacket.

Or, to explain it a different way, prosecutors stack up charges until the crime’s context has become so murky, and the length of the potential prison sentence has become so long, that the defendant has no choice but to sign a plea deal.

It’s a tactic often leveraged against people in lower income communities because it works. I know from personal experience. In fact, most of my friends are convicted felons who have served time at one point or another.

However, because my family didn’t have money to afford a lawyer, I had no choice but to cut my losses and sign a plea deal. After all, if I signed a plea deal, I would only lose a few months of my life. If I lost in court, I would lose five whole years of my life. In both cases, however, I would still become a convicted felon, forever stigmatized and trapped in the palm of the state. Checkmate.

Long Term Effects

Emphasizing incarceration instead of rehabilitation has only led to increased violence. In many states, overcrowding has forced prisons to house inmates in inhumane and dangerous conditions where inmates are often assaulted, raped, or even murdered.

How can society possibly expect a violent offender to come out rehabilitated when this is the violent environment they are sent into?

The consequences have been predictable. Many inmates develop post-traumatic stress disorder or reoffend within their first three years of release. According to the Bureau of Justice, some 76 percent of offenders will ultimately return to prison.

For many, the barricade to finding work and housing with a felony conviction is overwhelming, and sometimes even impossible to overcome, creating an incentive to reoffend and forcing taxpayers to foot the price tag for a revolving door.

I could have become one of those people. Yet when we compare statistics, violent offenders have some of the lowest recidivism rates of all re-offenders, while drug and property offenders have some of the highest.

Which again raises the question: If we are willing to entertain the idea of drug rehabilitation programs, then why not other types of rehabilitation programs? Such programs are not only more cost effective than the daily operations of a prison cell, but address the root of the problem, rather than ignore it.

Crime Trends and Second Chances

Victims’ rights advocates argue that mandatory minimum sentencing laws are behind the U.S.’s overall drop in crime over the decades (the past few years have been an exception). They argue these laws are necessary to curb gang violence and prevent rogue judges from setting otherwise dangerous criminals free.

However, what they fail to mention is that while the overall crime rate has dropped, states without mandatory minimum sentencing laws have also experienced a drop in crime during the same period.

Gang violence has also declined, despite recent short-term increases. In addition, many non-profit organizations have experienced tremendous success curbing violence with education and job training programs.

And while there are certainly examples of powerful judges freeing otherwise dangerous or lifelong criminals, there are likewise numerous examples of prosecutors abusing the same power to incarcerate otherwise innocent or redeemable people.

Next month will be 13 years that have passed since I was incarcerated. As one might expect, a lot has changed. On one hand, I’ve earned a degree in political science, launched a media company, and had the wonderful opportunity to write and speak for dozens of amazing national organizations.

On the other hand, not much has changed at all. I still get denied housing on a regular basis. I still get denied jobs outside of writing. And people still pass judgement.

How long is too long? How much is too much? I’m not a perfect human being. But I’m far from the person I was.

There is no question that low level drug offenders make up a significant portion of the prison population. The prison population, in fact, has increased eightfold since the U.S. declared a “war on drugs.”

However, with a prison population that also makes up almost a quarter of the world’s total incarcerated population, prison reform advocates would do well to emphasize the abolition of all mandatory minimum sentencing laws—not just ones related to drugs.