This column originally appeared in August 2020 to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the Chicano moratorium.

I need you to take a step back in time with me for a moment. I want you to go back 50 years ago to 1970. Before smartphones, before twenty-four-hour cable news, before social media or the global network that we would eventually come to know as the Internet would revolutionize the way we communicated.

While much has changed since 1970, in many ways the United States is still dealing with the same problems it was 50 years ago. From its involvement in a seemingly endless forever war, to dealing with rampant police brutality and racial violence, the United States is still largely fighting the same battles.

“He brought attention to the plights Chicanos faced, including discrimination, sub-standard education, contentious race relations, and police brutality.”

In 1970, the United States was in the middle of some of the worst social and political turmoil that it had ever experienced. The Anti-War Movement against the Vietnam War was at its peak, civil unrest and images of police brutality in cities across the country were being broadcasted into the living rooms of millions every night, and across the country militant political movements were fighting a struggle for community control and self-determination.

For Chicanos, the 1970s was also defined by change and the opportunity for new possibilities. The Chicano Power Movement was in full swing, and a new generation of young Chicano leaders and activists were increasingly expressing their political autonomy, cultural pride, and awareness, as well as challenging the assimilationist past values of the Mexican American identity.

New political organizations such as the Raza Unida Party were attempting to build electoral participation among Chicanos in the Southwest. Chicano students in East L.A. organized mass student walkouts, protesting the quality of education and unsatisfactory conditions in their schools, and self-defense groups like Brown Berets, inspired by Black Liberation groups like the Black Panthers brought attention to police brutality taking place in barrios throughout the country.

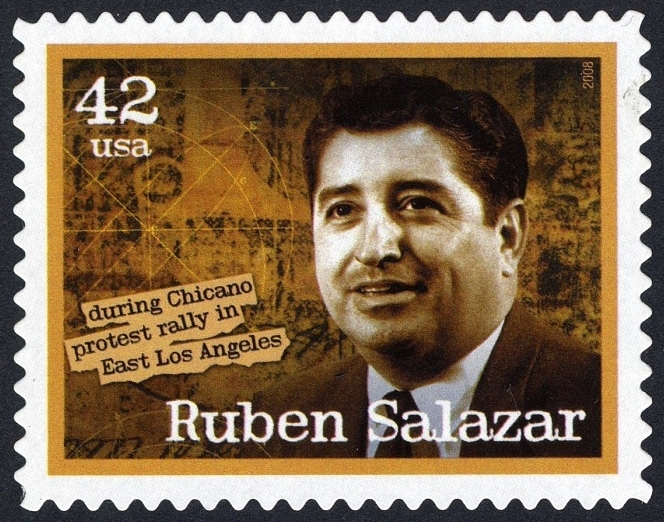

While the era marked a time of great change, one of its greatest champions covering these events at the time was Ruben Salazar. More importantly, he was one of the first Mexican American journalists from mainstream media to seriously cover the plight and struggles of the Chicano community.

Ruben Salazar, A Man of the People

Ruben Salazar was beyond a doubt, one, if not the most prominent Chicano journalists of his day. Born in Juárez, Mexico, and raised in El Paso, Texas, Salazar received his big career break when he joined The Los Angeles Times as a reporter in 1959.

At the L.A. Times, Salazar interviewed figures from César Chávez to Robert Kennedy and even President Dwight Eisenhower. Salazar would eventually leave the Times in January 1970 and serve as the news director of Los Angeles Spanish-language station KMEX-TV which further expanded his reach as a journalist.

As a columnist and news director, his reporting explored various issues affecting L.A.’s Mexican American community. He brought attention to the plights Chicanos faced, including discrimination, sub-standard education, contentious race relations, and police brutality.

As a result, Salazar was not without his detractors. It’s no secret that Salazar’s reporting, which often highlighted the racism and brutality inflicted by police against Chicano communities angered Los Angeles law enforcement officials, who had unsuccessfully tried to get him fired from his position at the Times.

In spite of the increasingly hostile relations between him and the police through his reporting, Salazar endeared himself to L.A.’s Chicano community and prominent figures within the Chicano Movement by reporting on both the movement’s achievements and shortcomings alike.

Salazar’s strong but candid support for the Chicano Movement would only further distinguish him from other journalists, and effectively position him as one of the few prominent Mexican American voices in mainstream news media. As an advocate and ally in the press, naturally, Salazar was assigned to cover the National Chicano Moratorium on that fateful day on August 29, 1970, his final assignment which would ultimately end in his untimely death.

Tragedy at the Chicano Moratorium

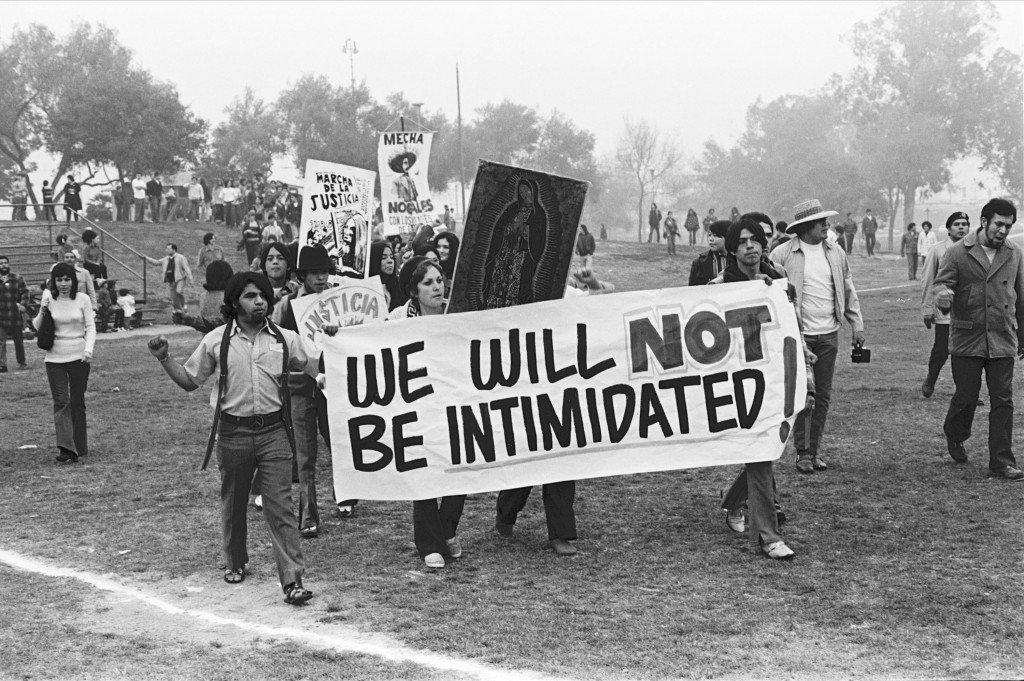

The Chicano Moratorium (formally known as the National Chicano Moratorium Committee Against The Vietnam War), was a movement of Chicano anti-war activists that assembled a broad coalition of Mexican American groups to organize opposition to the Vietnam War.

Led by local college activists, the Chicano student movement, and members of the Brown Berets, the Chicano Moratorium was a collective effort to raise awareness of the Vietnam War and police brutality as civil rights issues Chicanos faced.

On August 29, 1970, an estimated 20,000 to 30,000 participants from across the nation marched down Whittier Boulevard in East Los Angeles, eventually concluding at Laguna Park (since renamed Ruben Salazar Park).

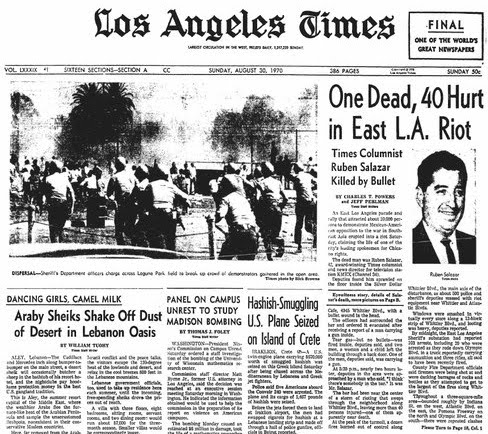

The rally would live in infamy as the peaceful, non-violent march and rally culminated in police violence. Broken up by law enforcement who claimed to have received reports that a nearby liquor store was being robbed, police chased the alleged ‘suspects’ into Laguna Park, declaring the thousands-strong demonstration an illegal assembly. Shortly after, the L.A. County Sheriff’s Department began shooting canisters of tear gas into the park as police violently clashed with demonstrators.

Among the thousands caught up in the chaos and confusion initiated by the police was Ruben Salazar, who had been reporting on the day’s events at the Moratorium. Seeking shelter, Salazar and a colleague sought shelter at the Silver Dollar Bar, a tiny dive bar on Whittier Boulevard where both had taken refuge from the tear gas and the havoc outside to have a drink.

According to witnesses, shortly after sitting down, Salazar was fatally struck in the back of the head by a tear gas canister.

It would later be revealed that the fatal shot was fired by L.A. County Sheriff’s deputy Thomas Wilson who claimed to have intended to shoot the projectile at a crowd but instead shot it into the Silver Dollar Bar—essentially transforming the tear gas canister into a lethal projectile.

Although a coroner’s inquest ruled Salazar’s death a homicide, Wilson was ultimately never prosecuted in Salazar’s death. At the time, Salazar’s death drew immediate suspicion, with many believing he had been deliberately targeted due to his prominent voice calling for police accountability.

Many still ascribe to the belief that the L.A. County Sheriff’s Department covered up Salazar’s death and engaged in a premeditated assassination plot to silence him. The L.A. County Sheriff still maintains that Salazar’s death was accidental and denies any accusations of foul play.

By the end of the moratorium, more than 150 demonstrators had been arrested, and three others along with Salazar had been killed in the pandemonium following the escalation by police. Salazar’s death would mark a turning point in the Chicano Movement, worsening the already strained relationship between the community and law enforcement in L.A.

The Legacy of Ruben Salazar

While many grievances of Salazar’s era such as the Vietnam War and a robust anti-war movement have long since subsided and faded into the dusty recesses of our society’s collective memory, nearly 50 years later many of the same injustices addressed at the Moratorium have remained stubbornly relevant.

Police brutality in communities of color is more common, or at the very least more documented than ever before.

Police violence and mistrust in law enforcement still remains a pervasive problem in Latino communities, who’ve felt the traumatizing legacy of police brutality. Concerns regarding surveillance by the state and freedom of the press are not only still relevant amid today’s contemporary struggles but, are perhaps even more dire now than they were in 1970. And in 2020, Chicanos and other Latinos still remain among some of the least educated and lowest-paid workers in the entire country.

Perhaps the greatest tragedy of Salazar’s death isn’t just that the life of a courageous, dedicated journalist was callously extinguished as a result of police violence and overzealousness, but how easily Salazar’s death could have been plucked from the headlines of today—especially as reporters, journalists, activists, and organizers alike still risk both their careers and lives seeking justice and demanding police accountability.

In an era where police are increasingly targeting reporters and journalists that cover their abuse with ever more frequency, it is nothing short of a miracle that this country has not already experienced a reprise of the same instance of police violence that so cruelly claimed Salazar’s life.

Since his untimely death, Salazar has become a hero among Chicano activists and widely regarded as a martyr of the Chicano Movement. Laguna Park, site of the Moratorium, has been renamed Salazar Park in Salazar’s honor, Salazar has been posthumously awarded a special Robert F. Kennedy Journalism Award, and in 2014, Salazar was even the subject of a PBS documentary.

Needless to say, fifty years since his untimely passing, Salazar’s influence and legacy still reverberate throughout our society.

Support Chicano/Latino Media. Subscribe For Only $1 Your First Month.

Today, there are more Chicano/Latino journalists and publications than Salazar could have ever dreamed of. As national Black Lives Matter demonstrations continue across the country and support for hard-hitting police reform continues to grow, Latino activists are increasingly joining a new generation of multiracial protests drawing attention to the same epidemic of police brutality within Latino communities that Salazar fought to cover in his reporting.

In the age of heightened awareness around police brutality and misconduct, many young Latinos are now vocally challenging the reluctance among community leaders to acknowledge racism and violence perpetrated by police against Latinos.

In 2020, the legacy of Ruben Salazar and the Chicano Moratorium serve as painful and powerful reminders of how far we have come, and how far we still have to progress. Salazar’s groundbreaking work as a journalist to give Chicanos proper representation in media has had a lasting impact on several generations of journalists since his passing.

And although many of the movements and conflicts of the 1970s have given way or evolved, the struggle for racial justice, civil rights, and an end to state violence against communities of color still persists, his legacy of speaking truth to power is perhaps more relevant now than ever before.

Get Stories Like This In Your Inbox

To receive weekly updates like this in your inbox, subscribe to The Daily Chela newsletter here.