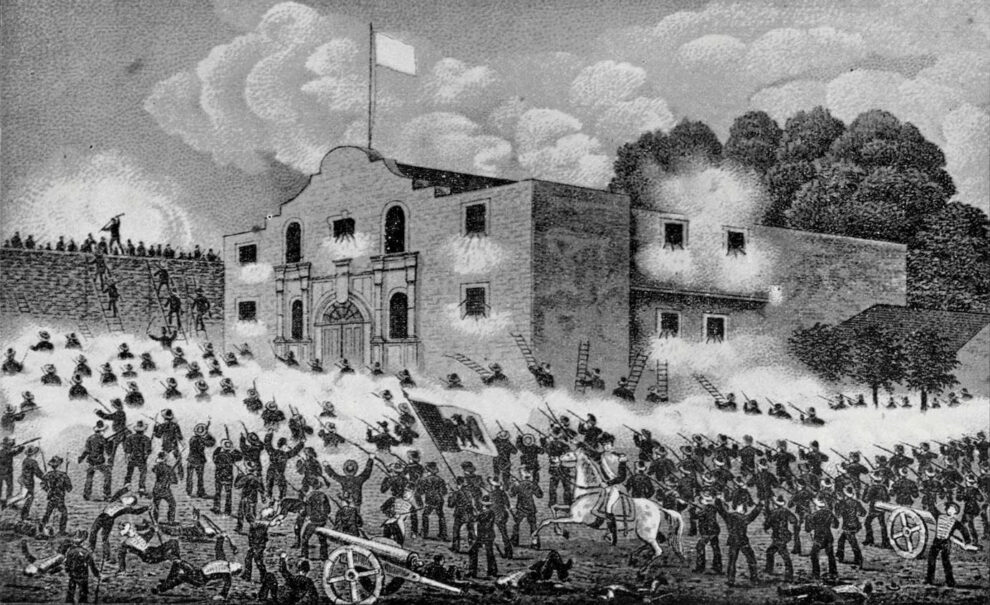

The Battle of the Alamo, Texas, is one of the most beloved and cherished episodes in the history of the United States, a building block in the construction of the nation, often told with the solemnity of a Battle of Jericho.

At the center of that narrative is the mythical figure of Davy Crockett, the explorer and freedom fighter who, according to the most widely accepted version, died fighting for Texas’ independence in 1836 against the Mexican hordes.

We could leave it there and forget about unnecessary entanglements. After all, Crockett is a real historical figure and it is true that he died in The Alamo, in the days when General Antonio López de Santa Anna razed the place.

But details matter, especially in the construction of colossal historical figures like Crockett, who stands out for his purity and his brave death as a warrior. That is why, a few decades ago, the discovery of an unknown diary written by one of General Santa Anna´s captains, a man named Enrique de la Peña, produced a heated controversy—to say the least—and a war of accusations that has not completely died out.

Forgery?

Why is the discovery of Captain Enrique de la Peña’s diary so important? Peña was an eyewitness to the battles of The Alamo and San Jacinto, a “new” voice on what really happened there. And according to the diary, Davy Crockett did not die fighting, but was captured alive when The Alamo surrendered, and after being held prisoner with other Texan rebels, he was slaughtered by the sword.

The finding is not “so” recent. De la Peña´s published manuscript appeared in Mexico in 1955 as La rebelión de Texas, manuscrito inédito de 1836, por un oficial de Santa Anna. The book was ignored by American scholars until it was translated in 1975 as With Santa Anna in Texas: A Personal Narrative of the Revolution, and published by the University of Texas.

The publication was followed by outrage and skepticism from those who felt disappointed to learn the truth about Crockett, to those who referred to the diary as an elaborate forgery made in the 20th century.

Inside the Alamo

When general Antonio López de Santa Anna arrived in the vicinity of San Antonio, there were between 180 and 250 fighters and several frightened citizens inside the Alamo. Santa Anna first sent a white-flagged messenger to offer defenders a chance to surrender, but before he arrived, William Travis, who was in charge of the fort, shot him. The act angered Mexicans, who planted a red flag meaning they would take no prisoners.

On March 5, the clash ended in a furious hand-to-hand combat, a moment that has passed into the imaginary of Texas as one of its most heroic episodes. Supposedly, Crockett and his men from Tennessee died defending one of the fortress walls until the end. “Here, am I, Colonel, assign us to some place, and I and my Tennessee boys will defend it all right,” Crockett allegedly said according to a version published in 1911. The embellished stories reported that dozens of dead Mexican soldiers were found around Crockett´s pierced body.

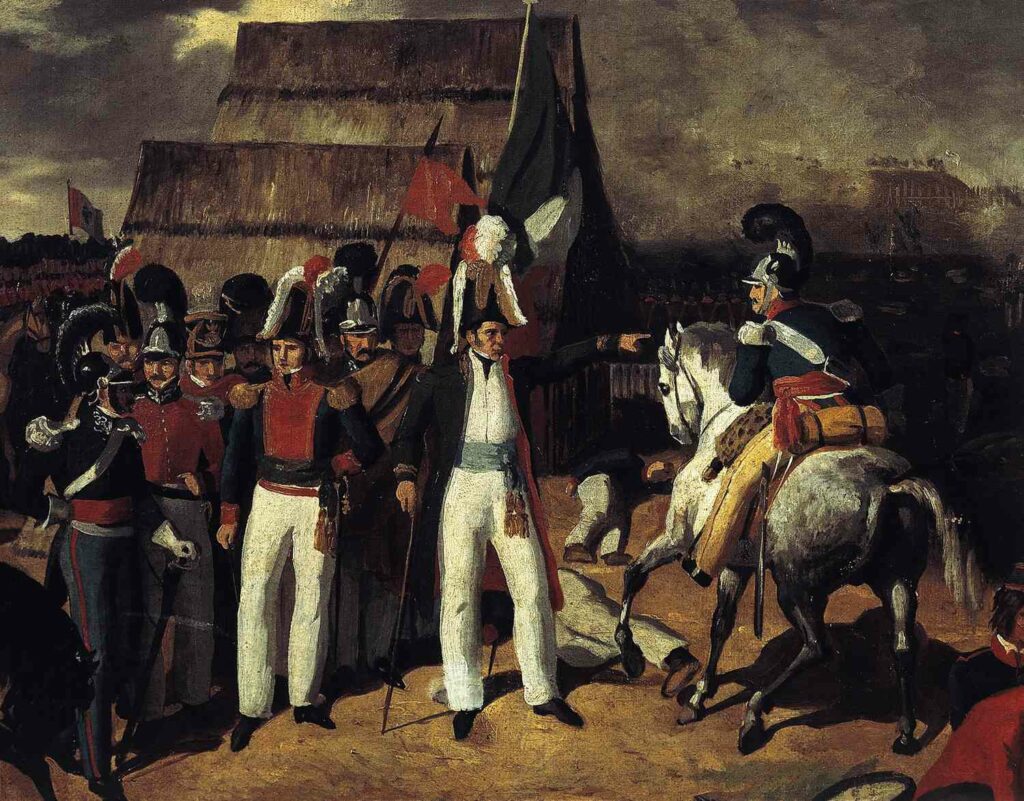

The appearance of the diary put to rest all the glorious descriptions of Davy Crockett´s last moments. According to De la Peña’s testimony, Crockett and a small group were captured and brought alive to the presence of Santa Anna.

“Some seven men had survived the general carnage and (…) they were brought before Santa Anna. Among them was one of great stature well proportioned with regular features, in whose face there was the imprint of adversity but in whom one also noticed a degree of resignation and nobility that did him honor. He was the naturalist David Crockett, well known in North America for his unusual adventures, who had undertaken to explore the country and who, finding himself in (San Antonio) Béjar at the very moment of surprise, had taken refuge in the Alamo fearing that his status as foreigner might not be respected. Santa Anna answered Castrillon’s intervention on Crockett´s behalf with a gesture of indignation and, addressing himself to (…) the troops closest to him, ordered his execution.”

De la Peña expresses horror and shame at what happened next. According to his testimony, the commanders were outraged at this order and did not support it, hoping that Santa Anna would cool down once the fury of the moment had passed. But the President’s personal guard, wanting to win his favor and flatter him, slaughtered the prisoners with their swords right on that spot.

“I turned away horrified in order not to witness such a barbarous scene”, wrote De la Peña, noting one last act of Crockett´s nobility: “Though tortured before they were killed, these unfortunates died without complaining and without humiliating themselves before their torturers.”

Reactions

Although de la Peña’s diary has been vilified by some, it is historically reliable, including the description of Crockett’s death. After all, its basic details fit with another published by Edward S. Ellis in 1884.

At last only six of the garrison were left alive. The officer shouted to them to surrender, promising that their lives should be spared. In the little group of Spartans were Davy Crockett and Travis, so exhausted they were scarcely able to stand. His face (Crockett´s) was crimson from a gash in his forehead, and nearly a score of Mexicans were stretched around him, either dead or dying from his fearful blows. There were a few brave and humane officers, and among them were General Castrillon and Bur dillon. They spoke sympathizingly to Crockett and Travis, and with several other officers walked to where the scowling Santa Anna stood and asked that the surrender of the few survivors might be received. The reply was an order that all should be shot.

After the unfortunate incident, all of the Alamo’s dead were stripped of their clothes, cut to pieces, and piled on top of each other. Then they were incinerated, a particularly humiliating fate. The ashes remained there for more than a year, until a party returned to put them inside a chest in March 1837, and buried them in a nearby site that to this day has not been found.

In the end, it doesn’t really matter if Davy Crockett died inside or outside the Alamo, shooting his rifle or shot by a squadron, or how many enemies he killed. The fact is that he shared the fate of his companions, and was ready to give up his life for a cause that he considered to be just.

That is, after all, what makes a hero.